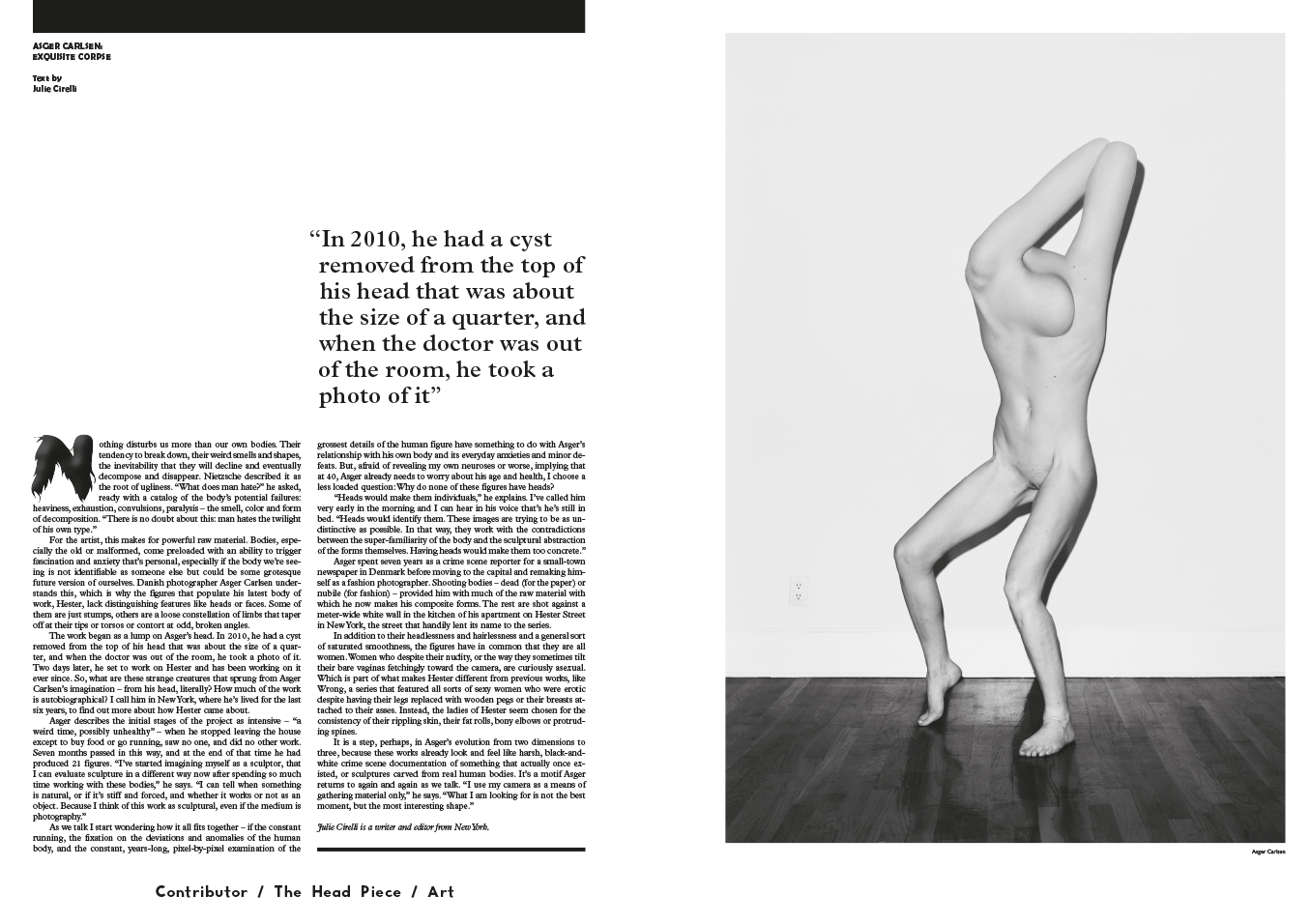

Nothing disturbs us more than our own bodies. Their tendency to break down, their weird smells and shapes, the inevitability that they will decline and eventually decompose and disappear. Nietzsche described it as the root of ugliness. “What does man hate?” he asked, ready with a catalog of the body’s potential failures: heaviness, exhaustion, convulsions, paralysis – the smell, color and form of decomposition. “There is no doubt about this: man hates the twilight of his own type.” For the artist, this makes for powerful raw material. Bodies, especially the old or malformed, come preloaded with an ability to trigger fascination and anxiety that’s personal, especially if the body we’re seeing is not identifiable as someone else but could be some grotesque future version of ourselves. Danish photographer Asger Carlsen understands this, which is why the figures that populate his latest body of work, Hester, lack distinguishing features like heads or faces. Some of them are just stumps, others are a loose constellation of limbs that taper off at their tips or torsos or contort at odd, broken angles.

By Julie Cirelli

The work began as a lump on Asger’s head. In 2010, he had a cyst removed from the top of his head that was about the size of a quarter, and when the doctor was out of the room, he took a photo of it. Two days later, he set to work on Hester and has been working on it ever since. So, what are these strange creatures that sprung from Asger Carlsen’s imagination – from his head, literally? How much of the work is autobiographical? I call him in New York, where he’s lived for the last six years, to find out more about how Hester came about.

Asger describes the initial stages of the project as intensive – “a weird time, possibly unhealthy” – when he stopped leaving the house except to buy food or go running, saw no one, and did no other work. Seven months passed in this way, and at the end of that time he had produced 21 figures. “I’ve started imagining myself as a sculptor, that I can evaluate sculpture in a different way now after spending so much time working with these bodies,” he says. “I can tell when something is natural, or if it’s stiff and forced, and whether it works or not as an object. Because I think of this work as sculptural, even if the medium is photography.”

As we talk I start wondering how it all fits together – if the constant running, the fixation on the deviations and anomalies of the human body, and the constant, years-long, pixel-by-pixel examination of the grossest details of the human figure have something to do with Asger’s relationship with his own body and its everyday anxieties and minor de- feats. But, afraid of revealing my own neuroses or worse, implying that at 40, Asger already needs to worry about his age and health, I choose a less loaded question:Why do none of these figures have heads?

“Heads would make them individuals,” he explains. I’ve called him very early in the morning and I can hear in his voice that’s he’s still in bed. “Heads would identify them. These images are trying to be as undistinctive as possible. In that way, they work with the contradictions between the super-familiarity of the body and the sculptural abstraction of the forms themselves. Having heads would make them too concrete.”

Asger spent seven years as a crime scene reporter for a small-town newspaper in Denmark before moving to the capital and remaking himself as a fashion photographer. Shooting bodies – dead (for the paper) or nubile (for fashion) – provided him with much of the raw material with which he now makes his composite forms. The rest are shot against a meter-wide white wall in the kitchen of his apartment on Hester Street in NewYork, the street that handily lent its name to the series.

In addition to their headlessness and hairlessness and a general sort of saturated smoothness, the figures have in common that they are all women.Women who despite their nudity, or the way they sometimes tilt their bare vaginas fetchingly toward the camera, are curiously asexual. Which is part of what makes Hester different from previous works, like Wrong, a series that featured all sorts of sexy women who were erotic despite having their legs replaced with wooden pegs or their breasts at- tached to their asses. Instead, the ladies of Hester seem chosen for the consistency of their rippling skin, their fat rolls, bony elbows or protrud- ing spines.

It is a step, perhaps, in Asger’s evolution from two dimensions to three, because these works already look and feel like harsh, black-and- white crime scene documentation of something that actually once ex- isted, or sculptures carved from real human bodies. It’s a motif Asger returns to again and again as we talk. “I use my camera as a means of gathering material only,” he says. “What I am looking for is not the best moment, but the most interesting shape.”

Julie Cirelli is a writer and editor from New York. This article was first published in our head piece issue (spring 2013)