A Matter Of Taste. Interview with Lou De Bètoly

By Philippe Pourhashemi

In 2022, the notions of good and bad taste may have become completely useless. Fashion is primarily a source of entertainment for most audiences, and clearly aimed at a hype-hungry public, which consumes hundreds of images on a daily basis. Magazines no longer dictate what people should wear and brands work directly with their consumers, who have in turn become docile influencers themselves.

Still, this mass discourse permeating fashion today does not necessarily imply that designers have stopped investigating the meanings behind our clothes and how fashion could make sense. Berlin-based French designer Lou de Bètoly belongs to an exciting wave of talents questioning the status quo, as well as looking for new ways to create collections beyond the usual calendars, while making them playful, unique, sustainable and smart at once.

That may seem like a lot to ask, but independent designers are facing a tough climate, which is not devoid of opportunities either. The industry has to change, and change comes from actual practice and concrete ideas, as opposed to vacant words. We caught up with Bètoly to discuss her subjective vision of fashion, letting go of stylistic categories and how art and craft get to meet up.

What is your background, and when did you move to Berlin?

I’m French and studied fashion at ESMOD, specializing in Haute Couture techniques and know-how. I worked within Jean-Paul Gaultier’s studio for two years and moved to Berlin ten years ago. I was only supposed to stay for six months at the beginning, but found myself happy and comfortable living here.

What are the key challenges you’ve faced with your own brand?

I’m passionate about artisanship, and the whole challenge for me has been to use craftsmanship in ways that could be replicated. Many pieces I produce are unique, and attitudes towards fashion have changed since the pandemic, too. Customers buy differently now and often want to know how something was made. They like to find out about the process as well, and even have a personal connection to the designer. So my line is split between one-off pieces and garments that can be produced in larger quantities.

Which opportunities did the lockdown bring you?

During the very first lockdown, I started working with art galleries here in Berlin. That was new and exciting for me. Recently, I got to work on a presentation with the König Galerie, which has an amazing space.

Would you say that textile research and innovation have an artistic dimension of their own?

I think it really depends on the framework, and what your audience expects. I think Haute Couture is very artistic, but what interests me is when a piece of textile is considered as art. I’m trying to investigate that fine line between art and craftsmanship.

Do you like to break sartorial codes within your work and explore new paths?

Definitely. French style tends to be on the conservative side and I love twisting traditional bourgeois codes, which are associated with what people in France refer to as ‘la province’. So I’ll mix cashmere with plastic, adding a decadent edge to luxury. There’s a certain irony to what I do, but no sarcasm at all.

Designer fashion has become increasingly commercial and luxury brands sell more and more overpriced sportswear. Do you think there’s still a niche interested in craft?

Yes, I believe that this customer exists, and compared to ten years ago, demands more craft and quality from clothes. It may be a limited audience, but I think it keeps growing every year.

Where did you grow up in France?

In Amiens. I’ve been obsessed with sartorial codes since childhood, and even though I grew up learning about them, I couldn’t stop questioning them. What is good taste? What is vulgar? When is something too short or too transparent? My aim is not to provoke people, but raise questions around these notions.

It’s interesting how good and bad taste seem completely irrelevant for a new generation, which is more focused on politics and social issues. Taste is subjective, but it cannot be categorized.

I agree. Trends disappear quicker, and there are more micro fads than ever before. I guess there’s also this nostalgia for ugly things, which qualifies as ironic consumption. Young people are obsessed with the 80s and early 90s, which were both defined by a certain kind of kitsch, way before minimalism made everything serious and more cerebral.

Where do you produce your clothes?

Everything I make is produced locally here. I used to love traveling around the globe to meet artisans and find new techniques to work on, but I stopped doing that since the pandemic started. For wholesale requests, I have local ateliers that can produce pieces for me, the only issue being that those types of companies don’t really like making complicated garments. I’d rather have control and do as much as I can in-house.

Do you collaborate with performers and celebrities, too?

I do, and love making custom-made outfits for artists. We have worked with the likes of Adele, Cindy Bruna, Regina Demina and Mathilde Fernandez. If you’re going to work on something that intricate and elaborate for a performer, it helps to know the personality and attitude of the wearer. Otherwise, it feels a bit like a sterile exercise. I do show my work in galleries, but fashion doesn’t exist without a body. Still, I would love to do full exhibitions in museums or take part within specific showcases.

Are you happy in Berlin?

I haven’t really thought about it to be honest. I just can’t imagine myself heading back to Paris though, so I guess I may have found the city that suits me.

Do you ever feel like a foreigner?

Yes, I do. Actually, I’m home when I go back to France, but don’t really belong to the culture anymore, so it’s a bizarre feeling you get being an expatriate. You’ll always be the foreigner somehow, but can’t fully relate to your roots either, it’s like this constant in-between.

I can fully relate to this, because I moved from Paris when I was 18 and can’t imagine living there ever again.

Paris became very gentrified, like most capital cities in Europe. Berlin is strange somehow, because there are quite a few brands here, but fashion does not feel as professional or important as it does in Paris. What I mean by this is that many designers don’t seem to take their craft seriously here, or maybe they just want to become commercial fast and sell a lot. Paris has this entire tradition and history with fashion, which does not exist here, so Berlin is relatively new and still naïve in those terms. And, of course, you don’t have all the codes here that you have in France.

Have you been approached by bigger brands to do collaborations?

Not yet, but I’d be very interested to work with brands specialized in certain types of products, like tights or legwear for instance. I’d be curious to see their machinery and find out more about their process.

What are your signature items within your collections?

I love working on knitwear separates, which allow me to combine crochet and embroidery with yarns. Those pieces have a precious and experimental feel, which I truly enjoy.

Do you sketch?

Not really. I like to work with materials directly and see where each piece takes me. That kind of creative freedom is really important for me.

You’ve done several fashion shows in the past. Would you like to return to the runway soon?

That’s a funny one, because I feel quite ambivalent about shows. On the one hand, I love the idea of putting a spectacle together and working on seasonal collections, but, on the other, it does not seem to make that much sense to me right now, because I’m currently not working in seasonal ways. That idea of two collections a year seems quite outdated to me, and I’ve been looking for alternatives. I also think that a great virtual presentation can get your message across as effectively as a runway show does. We need to be creative now, and find new ways to showcase fashion.

Do you like the idea of improvising and not knowing where something might go?

Actually, that is my process most of the time.

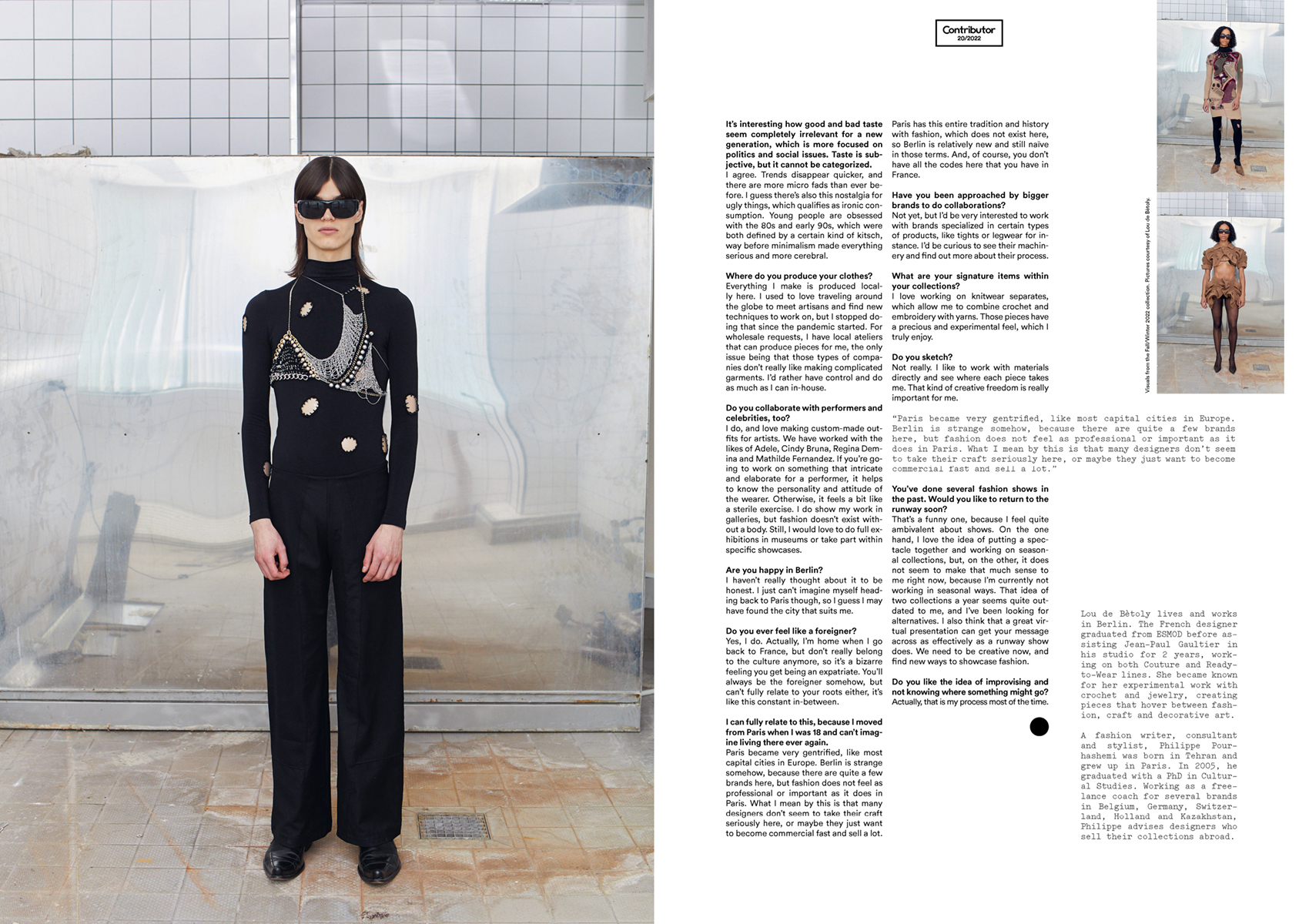

Lou de Bètoly lives and works in Berlin. The French designer graduated from ESMOD before assisting Jean-Paul Gaultier in his studio for two years, working on both Couture and Ready-to-Wear lines. She became known for her experimental work with crochet and jewelry, creating pieces that hover between fashion, craft and decorative art.

A fashion writer, consultant and stylist, Philippe Pourhashemi was born in Tehran and grew up in Paris. In 2005, he graduated with a PhD in Cultural Studies. Working as a freelance coach for several brands in Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Holland and Kazakhstan, Philippe advises designers who sell their collections internationally.