Ellis Island Artist Statement

By Stephen Wilkes

It is the dark side of the island.

A place where the huddled masses yearning to breathe free remained huddled, remained yearning, many permanently, just inches short of the Promised Land.

In the shadow of Ellis Island’s Great Hall, forgotten by history and woefully ill-equipped in its battle with nature, I came upon the ruins of a vast hospital: the contagious disease wards and isolation rooms for the people whose spirits carried them across oceans but whose bodies failed them, a stone’s throw from Paradise.

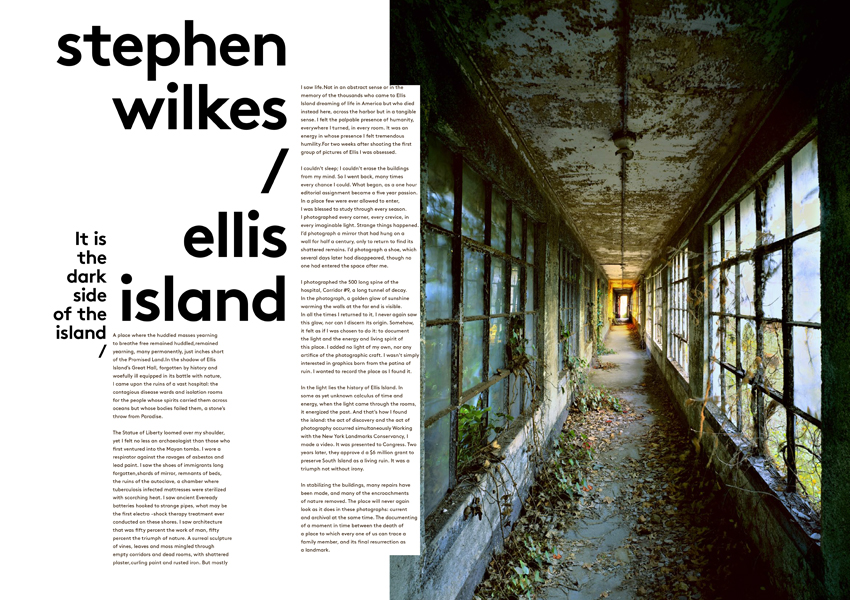

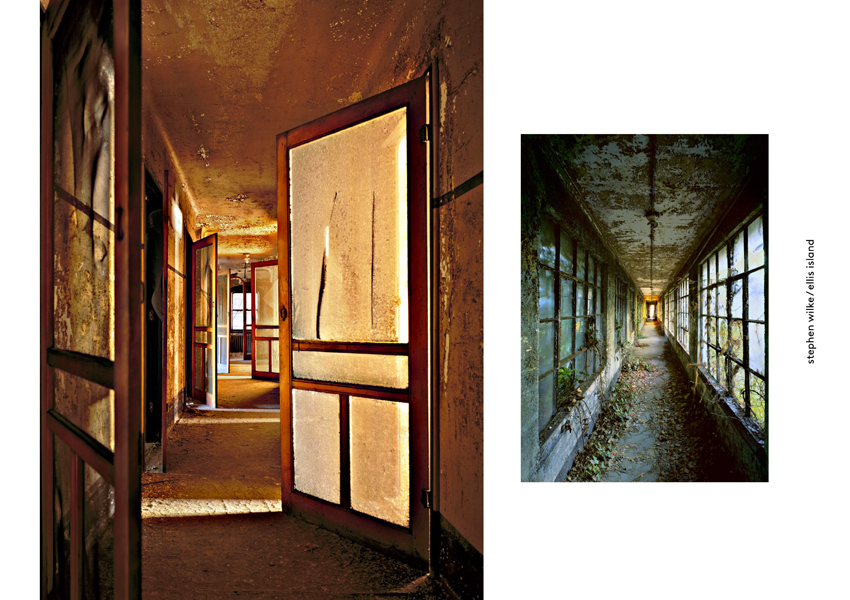

The Statue of Liberty loomed over my shoulder, yet I felt no less an archaeologist than those who first ventured into the Mayan tombs. I wore a respirator against the ravages of asbestos and lead paint. I saw the shoes of immigrants long forgotten, shards of mirror, remnants of beds, the ruins of the autoclave, a chamber where tuberculosis-infected mattresses were sterilized with scorching heat. I saw ancient Eveready batteries hooked to strange pipes, what may be the first electroshock therapy treatment ever conducted on these shores. I saw architecture that was fifty percent the work of man, fifty percent the triumph of nature. A surreal sculpture of vines, leaves and moss mingled through empty corridors and dead rooms, with shattered plaster, curling paint and rusted iron.

But mostly I saw life.

Not in an abstract sense — or in the memory of the thousands who came to Ellis Island dreaming of life in America but who died instead here, across the harbor — but in a tangible sense. I felt the palpable presence of humanity, everywhere I turned, in every room. It was an energy in whose presence I felt tremendous humility.

For two weeks after shooting the first group of pictures of Ellis I was obsessed. I couldn’t sleep; I couldn’t erase the buildings from my mind. So I went back, many times every chance I could. What began, as a one-hour editorial assignment became a five-year passion. In a place few were ever allowed to enter, I was blessed to study through every season. I photographed every corner, every crevice, in every imaginable light. Strange things happened. I’d photograph a mirror that had hung on a wall for half a century, only to return to find its shattered remains. I’d photograph a shoe, which several days later had disappeared, though no one had entered the space after me. I photographed the 500-long spine of the hospital, Corridor #9, a long tunnel of decay. In the photograph, a golden glow of sunshine warming the walls at the far end is visible. In all the times I returned to it, I never again saw this glow, nor can I discern its origin.

Somehow, it felt as if I was chosen to do it: to document the light and the energy and living spirit of this place. I added no light of my own, nor any artifice of the photographic craft. I wasn’t simply interested in graphics born from the patina of ruin. I wanted to record the place as I found it.

In the light lies the history of Ellis Island. In some as yet unknown calculus of time and energy, when the light came through the rooms, it energized the past. And that’s how I found the island: the act of discovery and the act of photography occurred simultaneously.

Working with the New York Landmarks Conservancy, I made a video. It was presented to Congress. Two years later, they approved a $6 million grant to preserve South Island as a living ruin. It was a triumph not without irony. In stabilizing the buildings, many repairs have been made, and many of the encroachments of nature removed. The place will never again look as it does in these photographs: current and archival at the same time. The documenting of a moment in time between the death of a place to which every one of us can trace a family member, and its final resurrection as a landmark.

This story by Stephen Wilkes was published in the print edition of our Death Issue