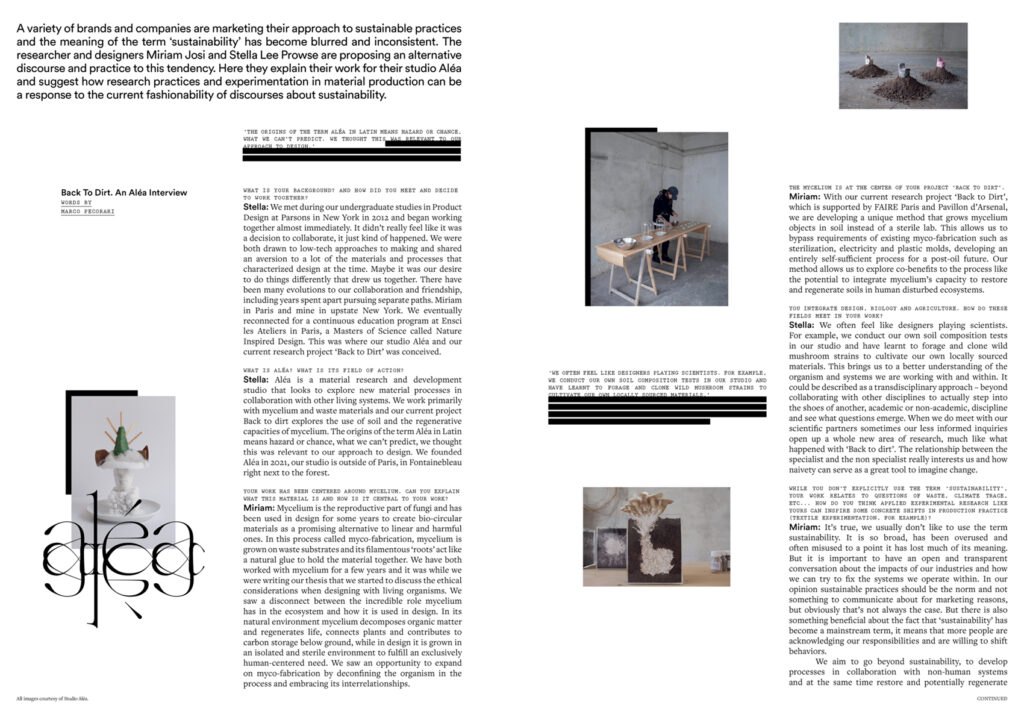

All images courtesy of Studio Aléa.

A variety of brands and companies are marketing their approach to sustainable practices and the meaning of the term ‘sustainability’ has become blurred and inconsistent. The researcher and designers Miriam Josi and Stella Lee Prowse are proposing an alternative discourse and practice to this tendency. Here they explain their work for their studio Aléa and suggest how research practices and experimentation in material production can be a response to the current fashionability of discourses about sustainability.

Interview by Marco Pecorari

WHAT IS YOUR BACKGROUND? AND HOW DID YOU MEET AND DECIDE TO WORK TOGETHER?

Stella: We met during our undergraduate studies in Product Design at Parsons in New York in 2012 and began working together almost immediately. It didn’t really feel like it was a decision to collaborate, it just kind of happened. We were both drawn to low-tech approaches to making and shared an aversion to a lot of the materials and processes that characterized design at the time. Maybe it was our desire to do things differently that drew us together. There have been many evolutions to our collaboration and friendship, including years spent apart pursuing separate paths. Miriam in Paris and mine in upstate New York. We eventually reconnected for a continuous education program at Ensci les Ateliers in Paris, a Masters of Science called Nature Inspired Design. This was where our studio Aléa and our current research project Back to Dirt was conceived.

WHAT IS ALÉA? WHAT IS ITS FIELD OF ACTION?

Stella: Aléa is a material research and development studio that looks to explore new material processes in collaboration with other living systems. We work primarily with mycelium and waste materials and our current project Back to Dirt explores the use of soil and the regenerative capacities of mycelium. The origins of the term Aléa in Latin means hazard or chance, what we can’t predict, we thought this was relevant to our approach to design. We founded Aléa in 2021, our studio is outside of Paris, in Fontainebleau right next to the forest.

YOUR WORK HAS BEEN CENTERED AROUND MYCELIUM. CAN YOU EXPLAIN WHAT THIS MATERIAL IS AND HOW IS IT CENTRAL TO YOUR WORK?

Miriam: Mycelium is the reproductive part of fungi and has been used in design for some years to create bio-circular materials as a promising alternative to linear and harmful ones. In this process called myco-fabrication, mycelium is grown on waste substrates and its filamentous ‘roots’ act like a natural glue to hold the material together. We have both worked with mycelium for a few years and it was while we were writing our thesis that we started to discuss the ethical considerations when designing with living organisms. We saw a disconnect between the incredible role mycelium has in the ecosystem and how it is used in design. In its natural environment mycelium decomposes organic matter and regenerates life, connects plants and contributes to carbon storage below ground, while in design it is grown in an isolated and sterile environment to fulfill an exclusively human-centered need. We saw an opportunity to expand on myco-fabrication by deconfining the organism in the process and embracing its interrelationships.

YOU INTEGRATE DESIGN, BIOLOGY AND AGRICULTURE. HOW DO THESE FIELDS MEET IN YOUR WORK?

Stella: We often feel like designers playing scientists. For example, we conduct our own soil composition tests in our studio and have learnt to forage and clone wild mushroom strains to cultivate our own locally sourced materials. This brings us to a better understanding of the organism and systems we are working with and within. It could be described as a transdisciplinary approach – beyond collaborating with other disciplines to actually step into the shoes of another, academic or non-academic, discipline and see what questions emerge. When we do meet with our scientific partners sometimes our less informed inquiries open up a whole new area of research, much like what happened with Back to Dirt. The relationship between the specialist and the non specialist really interests us and how naivety can serve as a great tool to imagine change.

WHILE YOU DON’T EXPLICITLY USE THE TERM ‘SUSTAINABILITY’, YOUR WORK RELATES TO QUESTIONS OF WASTE, CLIMATE TRACE, ETC… HOW DO YOU THINK APPLIED EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH LIKE YOURS CAN INSPIRE SOME CONCRETE SHIFTS IN PRODUCTION PRACTICE (TEXTILE EXPERIMENTATION, FOR EXAMPLE)?

Miriam: It’s true, we usually don’t like to use the term sustainability. It is so broad, has been overused and often misused to a point it has lost much of its meaning. But it is important to have an open and transparent conversation about the impacts of our industries and how we can try to fix the systems we operate within. In our opinion sustainable practices should be the norm and not something to communicate about for marketing reasons, but obviously that’s not always the case. But there is also something beneficial about the fact that ‘sustainability’ has become a mainstream term, it means that more people are acknowledging our responsibilities and are willing to shift behaviors.

We aim to go beyond sustainability, to develop processes in collaboration with non-human systems and at the same time restore and potentially regenerate depleted and even polluted environments. We are aware that regenerative design is a very ambitious goal and our research is still at a very early stage requiring a lot of R&D before it can be applied at a larger scale. But we think it is important to share our method even at this stage to invite others to contribute and move our research further or to inspire to develop other regenerative processes.

There is not one technology that will fix the fashion system or solve the climate crisis alone, what we need is a diversity of different holistic processes, approaches and alternative ways of coexisting and also the acknowledgement that we aren’t going to get it right every time – there has to be room for failure.

All images courtesy of Studio Aléa.

ALL YOUR PROJECTS SEEM TO GRAVITATE AROUND THE IDEA OF ‘EXPERIMENTAL MATERIALITY’. HOW IS THIS CONCEPT CENTRAL TO YOUR WORK?

Miriam: We use this term to describe our methodology in material research. We look to question perceptions of material value, this includes challenging aesthetic and also the idea of durability. Acknowledging that nothing is fixed and everything changes, ‘experimental materiality’ embraces process over product and celebrates impermanence.

Stella: Our work also challenges the concept of human mastery and more specifically the designer’s control over materials. Since the Industrial revolution humans have forged a one-sided relationship to the materials we work with where harsh toxic and energy intensive processes have allowed us to manipulate materials beyond their limits. Instead, we try to engage with the materials we work with as partners with an agency where designing becomes a constant exchange of taking and releasing control while aiming for a mutualistic symbiosis.

FOR ‘MADE IN SOIL’, YOU DEVELOPED A COLLABORATION WITH CAROLE COLLET OF LIVING SYSTEM LAB. CAN YOU TELL US A BIT MORE ABOUT THIS PROJECT?

Stella: To expand on our research in ‘Back to Dirt’ we were invited by Mathias Schwartz-Clauss the director of Domaine de Boisbuchet to collaborate with Carole Collet Co-Director of Living Systems Lab at Central Saint Martins UAL. The collaboration was for the exhibition titled Landscapes of Design, Women at the Heart of Domaine de Boisbuchet at Frac in Orleans.

The goal was to further develop the use of textile waste in our process growing objects in soil. Carole employed a wide range of fabric manipulation techniques which were inoculated and buried below ground, exploring the potential of textiles to act as an intermediate surface between the mycelium and the soil. Collaborations like this usually begin with a conversation, not one that surrounds any technical detail but instead around methodology and the peculiarities of working with living systems.

COLLABORATION IS CENTRAL TO YOUR WORK. HOW IS THIS CENTRAL TO DEVELOP AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH?

Stella: Collaboration is a central theme to our practice and it transcends working with each other, other disciplines and even the human – we consider mycelium as a collaborator and often ask questions like “what does the mycelium want?” Of course this is something we won’t ever know the answer to, but to consider it leaves open the possibilities of including shared benefits in our process. We borrow the term “bio-inclusive” from environmental philosopher Freya Mathews which reinstates humans and nature as one, acknowledging that our needs are deeply intertwined and the problem lies in there ever being a distinction.

All images courtesy of Studio Aléa.

EDUCATION IS A CENTRAL PRACTICE OF ALÉA IN MANY DIFFERENT WAYS. YOU DEVELOP WORKSHOPS AND YOU ARE BOTH TEACHERS. WHAT IS YOUR OPINION ABOUT EDUCATION AROUND QUESTIONS OF SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES?

Miriam: The workshops we do together as Aléa are centered around our methodology, which is based on holistic observation, collaboration and open-ended experimentation. We are both instructors at Parsons Paris, Stella is currently teaching Sustainable Systems, a required course for all First year students and I teach the Sustainability Seminar for the new MFA Fashion Design at the Arts. Teaching for us is a way of sharing our passion.

When we discuss sustainability with design students we are required to acknowledge the contradictions and injustices of our industries, society and daily lives. One of the main challenges is addressing the heavy, interconnected issues as well as navigating the anxieties and frustrations that come with their awareness without discouraging the students to take action and to apply responsible practices in their work. For this I think it is important to discuss and experiment with tangible and accessible technologies and solutions, which can be very empowering. The goal is to have students understand that there is power in acknowledging our limits and reconsider sustainability as an opportunity rather than a constraint.

HOW ARE YOUR RESEARCH/ARTISTIC PRACTICES INTEGRATED IN YOUR PEDAGOGICAL WORK?

Miriam: I think there is an urgent need for a mindset shift that embraces cooperation and resilience rather than competition and shaming. We incorporate short mycelium labs in our class curriculums. Working with mycelium can have huge pedagogical value in changing existing design paradigms. It can teach us countless lessons on circularity, resourcefulness, interdependence, caretaking and how to welcome failure and impermanence.

We recently taught a workshop at Domaine de Boisbuchet titled Beyond the Lab which gave us the chance to apply our methodology in a more holistic, expansive way. Being in a rural environment surrounded by wild fungi allowed for an immersive exploration of mycelium and our shared locality. We also wanted to consider more in depth the ethical questions in biodesign and explore how this inquiry can inform more reciprocal and integrated practices. aleawork.com

Dr. Marco Pecorari is Assistant Professor and Program Director of the MA in Fashion Studies at Parsons Paris where he teaches and conducts research on Fashion History and Theory. He is the author of several fashion books and a member of the Scientific Board of the European Fashion Heritage Association (EFHA).