Interview with Kaat Debo, Director of Antwerp’s Modemuseum

Despite being public places entered by countless visitors each year, fashion museums still depend on the singular and creative vision of their appointed curator, who will bring refreshing innovation, as well as smart distinction, to the exhibition process. Having acted as the director of Antwerp’s prestigious ModeMuseum, also known as MoMu, for more than a decade now, Kaat Debo epitomizes the figure of the young and enlightened curator, putting together original and informative shows, which satisfy industry insiders as well as a larger audience. Warm and passionate, Debo is clearly in her element when she talks about Belgian designers and their recent impact on fashion history. As a curator, she has to juggle between budget restrictions, physical limitations and time constraints, but she enjoys a challenge and has managed to turn MoMu into a cultural reference. Its brand new exhibition, entitled “Game Changers”, will be unveiled a few days before spring and seems to feature all the right elements to seduce her fans. We sat down with the talkative and humble curator to discuss her selection process for the museum, how she shops for the collection and what the challenges are when brands get involved.

By Philippe Pourhashemi

PHILIPPE POURHASHEMI: How are things looking for the new exhibition?

KAAT DEBO: We will start building up in a few days and there is still a lot to do, but we are on schedule and everything should work out fine. It usually takes around one month for us to build the actual space and install the garments afterwards.

How far in advance do you need to plan for a museum?

When we approach designers three of four years in advance to plan an exhibition with them, we rarely get a positive answer straight away. In 2020, there will be a Fashion Year project in Antwerp, which we are currently working on. The problem is that you need to communicate to tour operators a lot earlier in order to attract tourism. So they’re already asking us what’s going to happen in four years time, which makes it difficult because designers do not want to make decisions that early.

To curate is to make choices. Can you tell me about “Game Changers” and why you decided to focus on that theme?

The first idea for the exhibition came when I met Miren Arzalluz in New York, who works as a fashion historian and independent curator. I talked to Miren about how I wanted to do something around the Belgian and Japanese avant-garde of the 1980s, exploring the notion of a transformed female silhouette through new and radical proportions. The challenge was to make a younger audience understand that the avant-garde movement was itself influenced by previous designers who had often altered the female form, such as Vionnet, Poiret or Balenciaga. We took Balenciaga as the main game changer for this exhibition and examined how the silhouette changed throughout the 20th century.

There’s currently a lot of discussion around certain issues in the fashion industry and it seems that the game might also change quite soon. Did you make a connection between this and the exhibition?

Actually, I hadn’t thought about it before, but I agree it is a key preoccupation, which relates to our Zeitgeist. The question is: where is the fashion system heading?

Is there a correlation in fashion history between dramatic silhouettes and industry transformations?

I don’t think so. The silhouette today is not that drastic. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, people made much bolder choices when it came to their own wardrobe. The silhouette is much more conservative today. We may have more choice in fashion now, the look is not as extreme or dramatic as it used to be. When I worked with Walter Van Beirendonck on his exhibition here, he stressed the fact that students were more daring when he was doing fashion at the Academy. Even his buyers didn’t go for the same type of clothes when he started out, which means there are fewer risks taken in the industry now.

As a curator, are you more interested in statement pieces or do you also need to reflect the times?

When I select clothes for the private collection of the museum, there are several key factors that come into play. It’s not like there is one set of rules, even though we have what we call a “collection plan” and decide to focus on a specific area, which is Belgian fashion in our case. When I started working on the collection here, I didn’t start from scratch. There were already an archive and a collection when I came, so you always have in mind what other people selected and bought before you. You have to continue and update the collection in order to sustain its coherence.

Would it be a bit like a new designer entering an old house?

Exactly. You should respond to what happened before and look for pieces that complement it. We are still missing crucial pieces from the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s.

Where do you find these clothes?

It can be online, in vintage stores or through networks of private collectors we have relationships with. I also buy from fashion showrooms directly, but it’s sometimes difficult to know when you should start purchasing certain designers. Can they be relevant or important from their very first collections? Good curating is about clear choices, otherwise your collection goes allover the place.

Do you trust your instinct then?

I don’t know if you can feel this, but you need to compare to what you already own in your collection. For example, I haven’t purchased a look from VETEMENTS yet, but I’ve been doubting whether or not I should have bought them from the first season. I guess I want to wait a little longer and see how it evolves, you never know what could happen later and if the brand will still be in existence. Some museums have a policy whereby they don’t buy anything if the brand is not at least 10 years old, but I’m not that strict when it comes to purchasing. So it’s instinct and budget as well. I cannot buy from each designer every season, I get pieces that are in line with the signature style of the designer and reflect his or her own aesthetics. Is the look I buy representative of the brand’s DNA or not?

Sometimes I buy with a specific exhibition in mind already. In 2018, we will start displaying our permanent collection in an additional space and I need to make sure there is enough in the collection to guarantee a regular rotation of looks. It’s important to know what designers themselves have in their archive in order to negotiate with them. When they retire and have issues storing their clothes, they sometimes contact us to see if we can keep them as long-term loans, which is different from donation. Of course we are not a free storage space and there are rules behind each loan, but it’s good for designers to know that their clothes will be well looked after here. They often realize that when they come to view our archive.

Did you buy Raf Simons when he was designing at Dior?

We did. Relevance is not always linked with time and how long a designer stays in a specific house. We also bought what Raf designed at Jil Sander and again I regret now having bought more. I didn’t know that at Jil Sander they were not keeping a good archive, even though Raf has some pieces himself. Basically I wish I had purchased more, especially the last two collections, which I thought were really significant. We were buying from the press samples then and had to wait for six months before seeing what was still available. Dries and Ann have, for instance, great archives, which makes my job a lot easier. Dries donates pieces to the museum each season and makes sure that we don’t buy what he’s willing to give us, which means there is no overlapping.

You will probably buy Demna for Balenciaga then, even though he is not a Belgian designer, but studied at the Royal Academy here.

Yes, I probably will, as it is an important move. Our policy is Belgian fashion design and we’re getting into this touchy issue of national identity, which in itself is a commercial argument. Can a designer who studied at a Belgian school, but lives and works elsewhere, still be considered for our collection? 95% of the designers graduating here are not from Antwerp and they are not Belgian either, but they will probably still communicate about being an “Antwerp designer” as it’s interesting for them commercially and has an impact on how the industry perceives them.

Do the political and the cultural mix in that sense?

I wouldn’t name it as “political”, but I’m aware that national identity has a commercial value. Look at Maison Martin Margiela, which was originally a Belgian brand that was sold to an Italian group. Martin left the company and now we have a British designer heading the creative studio. In twenty years time, no one will probably remember that Martin Margiela was a Belgian brand, and fashion people tend to forget things easily.

It’s called “fashion amnesia”.

The label may refer to Belgian identity in a way, but Martin is no longer included in the name. It’s “Maison Margiela” now and not “Maison Martin Margiela”.

Are you usually more successful with thematic or designer exhibitions?

The designer shows are more successful because you already have a name that is known and recognized by people, so it’s much easier in terms of marketing. Getting a theme across is always more challenging. Names work better than themes.

When you develop such exhibitions, are the brands involved financially?

They can be, and I am not against houses participating. Some argue that it damages the objectivity of the curator, but sometimes you need to the brands to help you access their archive and put the exhibition together, so I see it more as a useful collaboration to ensure the best results. If we have the possibility, we prefer to engage with designers and houses on a fuller level, which means the end result will be powerful. It’s difficult to do everything by yourself and this applies to museums, too. There are however instances where exhibitions were organized independently and the houses in question were not pleased with the results.

Was it about losing control?

Some houses like to be involved when their own history is being written and it is a tricky exercise. If you are a museum and own a great collection of a specific designer, why shouldn’t you do your own exhibition independently? At the same time, collaborating with a brand can be quite inspiring and interesting as a process.

I remember visiting the Gucci museum a few years ago and found it amusing that all traces of Tom Ford had been completely erased. It definitely felt like a political act.

It is their right of course to write their own history, but people will still expect a sense of history from a museum, which I find rather problematic. As a museum, our task is to write history, and even though complete objectivity does not exist, because you always have a bias and come from a specific background, you still try to do it in an academic way, which does justice to what has happened. I guess you need to be respectful.

You do not have the budget or resources that museums in London, New York or Paris may enjoy. Why do you think the MoMu’s exhibitions have been so popular?

You want good objects in your exhibitions, but there are limits to what you can afford and physically store in your space. Fortunately, we are close to London and Paris, which makes the loaning process a lot easier. Ultimately, it’s not about money, but the narrative you create and how substantial it is. We do all our productions ourselves and the MoMu changes every time a new exhibition takes place. You will have to find a good story, but it also needs to be exciting visually, and I’m glad we have managed to do that.

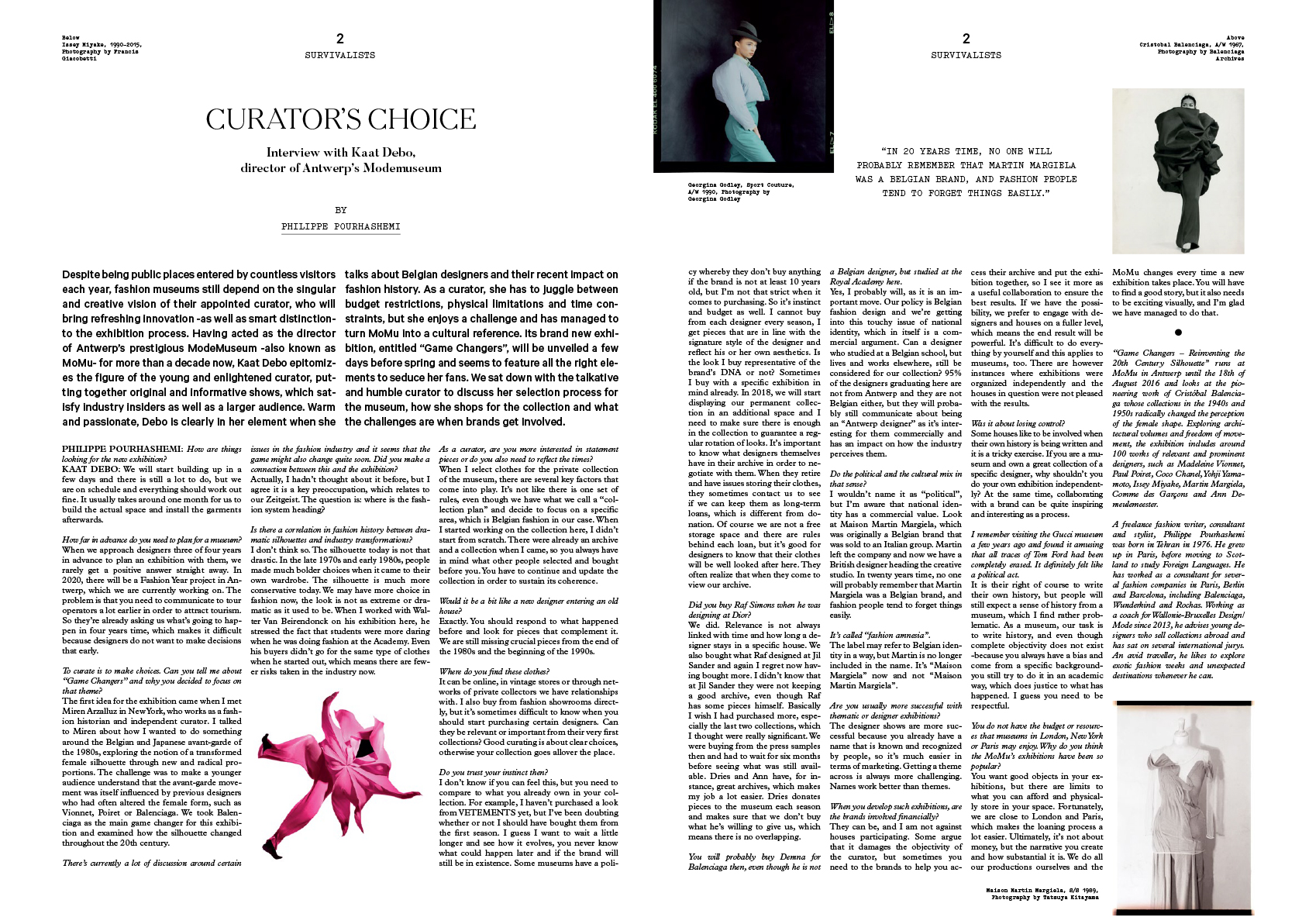

“Game Changers – Reinventing the 20th Century Silhouette” runs at MoMu in Antwerp until the 18th of August 2016 and looks at the pioneering work of Cristóbal Balenciaga whose collections in the 1940s and 1950s radically changed the perception of the female shape. Exploring architectural volumes and freedom of movement, the exhibition includes around 100 works of relevant and prominent designers, such as Madeleine Vionnet, Paul Poiret, Coco Chanel, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, Martin Margiela, Comme des Garçons and Ann Demeulemeester.

A freelance fashion writer, consultant and stylist, Philippe Pourhashemi was born in Tehran in 1976. He grew up in Paris, before moving to Scotland to study Foreign Languages. He has worked as a consultant for several fashion companies in Paris, Berlin and Barcelona, including Balenciaga, Wunderkind and Rochas. Working as a coach for Wallonie-Bruxelles Design/ Mode since 2013, he advises young designers who sell collections abroad and has sat on several international jurys. An avid traveller, he likes to explore exotic fashion weeks and unexpected destinations whenever he can.