Interview with historian Olivier Saillard

Collecting fashion in museums is more than just gathering an assemblage of clothing into an archive. Political, class, gender, aesthetical and geographical impositions are behind each garment conserved in museums. But there is more. Not only garments but also many other materials and immaterial practices must be considered when we collect fashion in museums. It is about all these matters that Olivier Saillard, the director of the Palais Galliera (the Musée de la Mode) in Paris since 2010, speaks in this interview. After having worked for the Costume Museum in Marseille and Les Arts Décoratifs in Paris, Saillard is today one of the most celebrated international fashion curators. On the side of his celebrated exhibitions like Madame Grès: Couture at Work held at Musée Bourdelle in 2011 or retrospectives on Azzedine Alaïa and Lanvin, Saillard has recently attracted public attention with a series of performances, especially famous are the one in collaboration with the actress Tilda Swinton, that problematize the meanings of collecting, conserving and exhibiting fashion in museums.

By Marco Pecorari

Marco Pecorari: Since this issue of Contributor Magazine focuses on “Casting and Collections” I would like to start with your performance Models Never Talk, firstly performed at Milk Studios New York in 2014, which does not only speak about models but also about the difficulties of collecting immaterial practices that circulate in the fashion industry. How did you come up with this idea?

Olivier Saillard: The idea starts with my very first performance Salon de couture with the model Violeta Sanchez, shown 10 years ago. It was a show without clothes, just with a speaker reading poetic descriptions of garments as the way of haute couture presentations does. Then, in 2007, with eight models, we did the Sosies performance, about gestures of the models and how the designers have carved their attitude. But the models did not speak. Models Never Talk gave them their voices back.

MP: Although you already had collaborated with some of the models for previous performances, there are also new models. How did the casting of Models Never Talk go? What were the criteria of selection of the models?

OS: By word of mouth and friendship. Violeta Sanchez was the first model I worked with. Then she talked to others like Claudia Huidobro, Axelle Doué, Amalia Vairelli, Anne Rohart, then Suzanne Moncur, Johanna Preiss and of course Marie Senec and Dauphine de Jerphanion.

MP: While in Models At Work at Victoria & Albert Museum in London 2012, the models were walking on catwalk re-enacting gestures and poses, in Models Never Talk models perform as sort of fashion anamnesis, being asked to recall their memories about their work for famous designers like Yves Saint Laurent or Thierry Mugler. In this performance, they are required to act rather than simply model. Did this represent a challenge for you or the models?

OS: Most of the models weren’t comfortable talking because they are not used to it, but by working on their memories I think they won this challenge.

MP: Models Never Talk is one of the many performances you have created. When did you start working with this format? Was there any particular story that pushed towards this?

OS: Working in the museum I quickly felt oppressed. Around 2002, I decided to write poems on post-it notes and fax them to fashion editors. The poems were about stories surrounding clothes that I found in news clippings having to do with death. I wrote about these pieces of clothing that were used as instruments to commit suicide, like a tie, or a belt for example.

MP: What is the creative process of these performances? How do you create them in terms of choreography and scenography?

OS: I have no other inspiration than the girls themselves. The memories of movements and attitudes according to each designer made the scenography.

MP: How did the collaborations with Tilda Swinton begin for the performances like The Impossible Wardrobe at Palais du Tokyo in 2012 in Paris?

OS: It started thanks to a common friend, the photographer Katerina Jebb. We met and shared ideas and projects.We still do.

MP: You also appear in your performances. How do you envision your presence on stage?

OS: As a conductor we can’t see.

MP: All your performances seem to problematize a more conventional way to think about fashion in museums. I am thinking about The Cloakroom at Galliera in 2014 where you discussed the poetics of everyday garments which are not at the centre of museum’s collecting practices. Do you see these performances as another way to work as curator?

OS: Of course. It nourishes it.

MP: Do you think it is limiting to think of fashion in material terms, can we provocatively think of a fashion museum without garments?

OS: I don’t think so, but it would be a challenge. But, a museum of garments without clothes?

MP: What are the biggest challenges you face as Director of Galliera?

OS: I don’t understand challenges. I just do my work and save the memory of those who counts for the history of fashion.

MP: Does the museum have a critical duty towards the fashion system since media are often denounced to be uncritical towards the industry’s practices?

OS: The Museum is the critical zone made of independency. It should be a mirror of fashion.

MP: Could you explain the practice of collecting garments for your museum? For instance, what are the challenges of collecting contemporary fashion?

OS: The collection has been constructed by purchase and generous gifts. Since about 10 years, we have been more selective for the gifts according to their condition, aesthetic and importance for fashion history. Collecting fashion is about the present. We have to step backwards to think about fashion, but in the meantime not missing the opportunity of collecting at the moment of the creation.

MP: What would you like to add to the Galliera that you are not allowed to collect?

OS: I have no interdiction but we have to argue about each piece we accept or buy for the Museum. We have never bought an entire collection. I wish it could be Comme des Garçons by Rei Kawakubo.

MP: In your exhibitions, you are, to some extent, casting garments from your museums’ collections. What makes you opt for a garments or another? Is it only an historical perspective or is there more?

OS: There are also other sides to selecting a piece. Sometimes the condition brings poetry and fragility, even if she hasn’t be worn by a celebrity.

MP: Do you have a favourite piece in the collection?

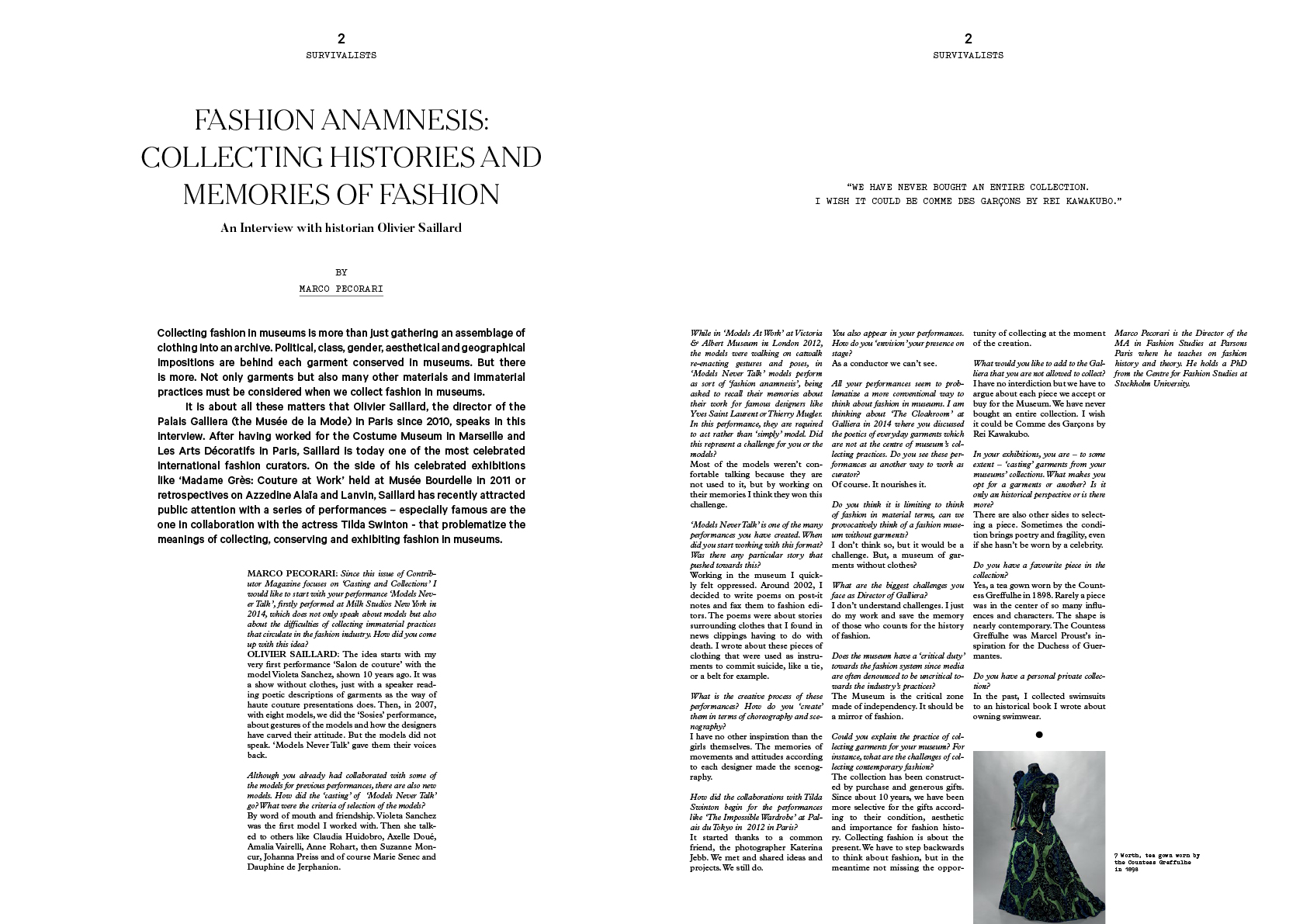

OS: Yes, a tea gown worn by the Countess Greffulhe in 1898. Rarely a piece was in the center of so many influences and characters. The shape is nearly contemporary. The Countess Greffulhe was Marcel Proust’s inspiration for the Duchess of Guermantes.

MP: Do you have a personal private collection?

OS: In the past, I collected swimsuits for an historical book I wrote about owning swimwear.

Marco Pecorari is the Director of the MA in Fashion Studies at Parsons Paris where he teaches on fashion history and theory. He holds a PhD from the Centre for Fashion Studies at Stockholm University.