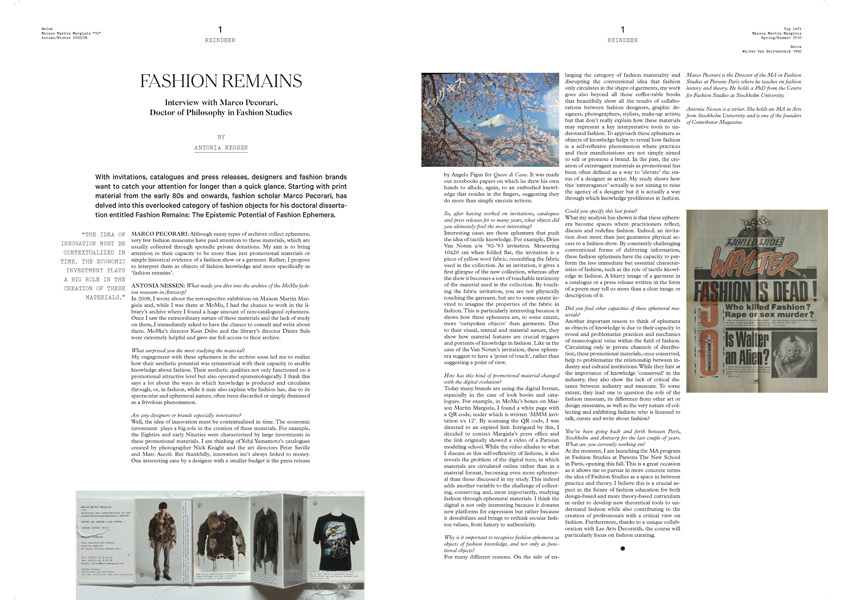

FASHION REMAINS

Interview with Marco Pecorari, Doctor of Philosophy in Fashion Studies

With invitations, catalogues and press releases, designers and fashion brands want to catch your attention for longer than a quick glance. Starting with print material from the early 80s and onwards, fashion scholar Marco Pecorari, has delved into this overlooked category of fashion objects for his doctoral dissertation entitled Fashion Remains: The Epistemic Potential of Fashion Ephemera.

By Antonia Nessen

MARCO PECORARI: Although many types of archives collect ephemera, very few fashion museums have paid attention to these materials, which are usually collected through sporadic private donations. My aim is to bring attention to their capacity to be more than just promotional materials or simple historical evidence of a fashion show or a garment. Rather, I propose to interpret them as objects of fashion knowledge and more specifically as ‘fashion remains’.

ANTONIA NESSEN: What made you dive into the archive of the MoMu fashion museum in Antwerp?

In 2008, I wrote about the retrospective exhibition on Maison Martin Margiela and, while I was there at MoMu, I had the chance to work in the library’s archive where I found a huge amount of non-catalogued ephemera. Once I saw the extraordinary nature of these materials and the lack of study on them, I immediately asked to have the chance to consult and write about them. MoMu’s director Kaat Debo and the library’s director Dieter Suls were extremely helpful and gave me full access to their archive.

What surprised you the most studying the material?

My engagement with these ephemera in the archive soon led me to realize how their aesthetic potential was symmetrical with their capacity to enable knowledge about fashion.Their aesthetic qualities not only functioned on a promotional attractive level but also operated epistemologically. I think this says a lot about the ways in which knowledge is produced and circulates through, or, in fashion, while it may also explain why fashion has, due to its spectacular and ephemeral nature, often been discarded or simply dismissed as a frivolous phenomenon.

Are any designers or brands especially innovative?

Well, the idea of innovation must be contextualized in time. The economic investment plays a big role in the creation of these materials. For example, the Eighties and early Nineties were characterized by large investments in these promotional materials. I am thinking of Yohji Yamamoto’s catalogues created by photographer Nick Knight and the art directors Peter Saville and Marc Ascoli. But thankfully, innovation isn’t always linked to money. One interesting case by a designer with a smaller budget is the press release by Angelo Figus for Quore di Cane. It was made out notebooks papers on which he drew his own hands to allude, again, to an embodied knowledge that resides in the fingers, suggesting they do more than simply execute actions.

So, after having worked on invitations, catalogues and press releases for so many years, what objects did you ultimately find the most interesting?

Interesting cases are those ephemera that push the idea of tactile knowledge. For example, Dries Van Noten a/w ’92-’93 invitation. Measuring 10×20 cm when folded flat, the invitation is a piece of yellow wool fabric, resembling the fabric used in the collection. As an invitation, it gives a first glimpse of the new collection, whereas after the show it becomes a sort of touchable testimony of the material used in the collection. By touching the fabric invitation, you are not physically touching the garment, but are to some extent invited to imagine the properties of the fabric in fashion.This is particularly interesting because it shows how these ephemera are, to some extent, more ‘outspoken objects’ than garments. Due to their visual, textual and material nature, they show how material features are crucial triggers and portents of knowledge in fashion. Like in the case of the Van Noten’s invitation, these ephemera suggest to have a ‘point of touch’, rather than suggesting a point of view.

How has this kind of promotional material changed with the digital evolution?

Today many brands are using the digital format, especially in the case of look books and catalogues. For example, in MoMu’s boxes on Maison Martin Margiela, I found a white page with a QR code, under which is written ‘MMM invitation s/s 12’. By scanning the QR code, I was directed to an expired link. Intrigued by this, I decided to contact Margiela’s press office and the link originally showed a video of a Parisian modeling school. While the video alludes to what I discuss as this self-reflexivity of fashion, it also reveals the problem of the digital turn, in which materials are circulated online rather than in a material format, becoming even more ephemeral than those discussed in my study. This indeed adds another variable to the challenge of collecting, conserving and, most importantly, studying fashion through ephemeral materials. I think the digital is not only interesting because it donates new platforms for expression but rather because it destabilizes and brings to rethink secular fashion values, from luxury to authenticity.

Why is it important to recognize fashion ephemera as objects of fashion knowledge, and not only as functional objects?

For many different reasons. On the side of enlarging the category of fashion materiality and disrupting the conventional idea that fashion only circulates in the shape of garments, my work goes also beyond all those coffee-table books that beautifully show all the results of collaborations between fashion designers, graphic designers, photographers, stylists, make-up artists; but that don’t really explain how these materials may represent a key interpretative tools to understand fashion.To approach these ephemera as objects of knowledge helps to reveal how fashion is a self-reflexive phenomenon where practices and their manifestations are not simply aimed to sell or promote a brand. In the past, the creation of extravagant materials as promotional has been often defined as a way to ‘elevate’ the status of a designer as artist. My study shows how this ‘extravagance’ actually is not aiming to raise the agency of a designer but it is actually a way through which knowledge proliferates in fashion.

Could you specify this last point?

What my analysis has shown is that these ephemera become spaces where practitioners reflect, discuss and redefine fashion. Indeed, an invitation does more than just guarantee physical access to a fashion show. By constantly challenging conventional forms of delivering information, these fashion ephemera have the capacity to perform the less immediate but essential characteristics of fashion, such as the role of tactile knowledge in fashion. A blurry image of a garment in a catalogue or a press release written in the form of a poem may tell us more than a clear image or description of it.

Did you find other capacities of these ephemeral materials?

Another important reason to think of ephemera as objects of knowledge is due to their capacity to reveal and problematize practices and mechanics of museological value within the field of fashion. Circulating only in private channels of distribution, these promotional materials, once conserved, help to problematize the relationship between industry and cultural institutions. While they hint at the importance of knowledge ‘conserved’ in the industry, they also show the lack of critical distance between industry and museum. To some extent, they lead one to question the role of the fashion museum, its difference from other art or design museums, as well as the very nature of collecting and exhibiting fashion: who is licensed to talk, curate and write about fashion?

You’ve been going back and forth between Paris, Stockholm and Antwerp for the last couple of years. What are you currently working on?

At the moment, I am launching the MA program in Fashion Studies at Parsons The New School in Paris, opening this fall. This is a great occasion as it allows me to pursue in more concrete terms the idea of Fashion Studies as a space in between practice and theory. I believe this is a crucial aspect in the future of fashion education for both design-based and more theory-based curriculum in order to develop new theoretical tools to un- derstand fashion while also contributing to the creation of professionals with a critical view on fashion. Furthermore, thanks to a unique collaboration with Les Arts Decoratifs, the course will particularly focus on fashion curating.

Marco Pecorari is the Director of the MA in Fashion Studies at Parsons Paris where he teaches on fashion history and theory. He holds a PhD from the Centre for Fashion Studies at Stockholm University.

Antonia Nessen is a writer. She holds an MA in Arts from Stockholm University and is one of the founders of Contributor Magazine.