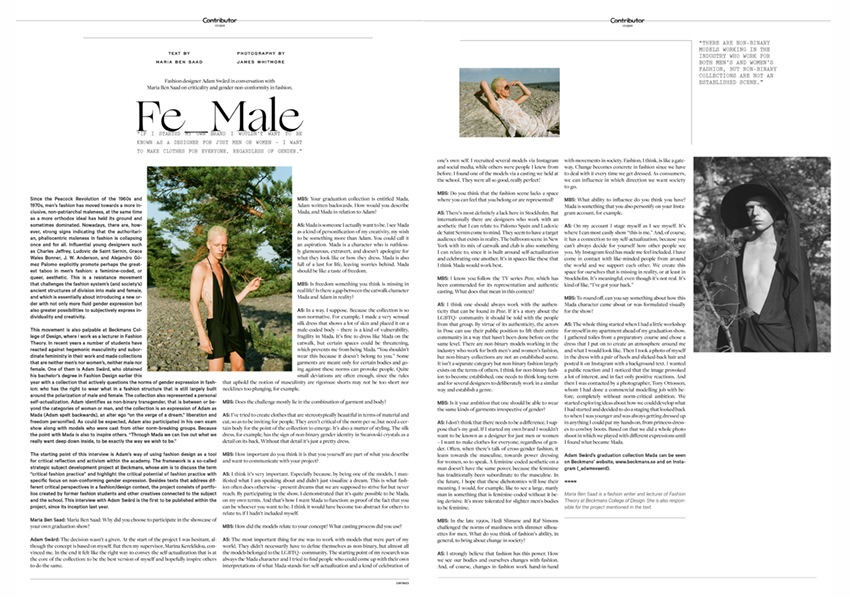

Fe_Male

Fashion designer Adam Swärd in conversation with Maria Ben Saad on criticality and gender non-conformity in fashion.

By Maria Ben Saad

Since the Peacock Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, men’s fashion has moved towards a more inclusive, non-patriarchal maleness, at the same time as a more orthodox ideal has held its ground and sometimes dominated. Nowadays, there are, however, strong signs indicating that the authoritarian, phallocentric maleness in fashion is collapsing once and for all. Influential young designers such as Charles Jeffrey, Ludovic de Saint Sernin, Grace Wales Bonner, J. W. Anderson, and Alejandro Gómez Palomo explicitly promote perhaps the greatest taboo in men’s fashion: a feminine-coded, or queer, aesthetic. This is a resistance movement that challenges the fashion system’s (and society’s) ancient structures of division into male and female, and which is essentially about introducing a new order with not only more fluid gender expression but also greater possibilities to subjectively express individuality and creativity.

This movement is also palpable at Beckmans College of Design, where I work as a lecturer in Fashion Theory. In recent years a number of students have reacted against hegemonic masculinity and subordinate femininity in their work and made collections that are neither men’s nor women’s, neither male nor female. One of them is Adam Swärd, who obtained his bachelor’s degree in Fashion Design earlier this year with a collection that actively questions the norms of gender expression in fashion: who has the right to wear what in a fashion structure that is still largely built around the polarizing of male and female. The collection also represented a personal self-actualization. Adam identifies as non-binary transgender, that is between or beyond the categories of woman or man, and the collection is an expression of Adam as Mada (Adam spelt backwards), an alter ego “on the verge of a dream,” liberation and freedom personified. As could be expected, Adam also participated in his own exam show along with models who were cast from other norm-breaking groups. Because the point with Mada is also to inspire others. “Through Mada we can live out what we really want deep down inside, to be exactly the way we wish to be.”

The starting point of this interview is Adam’s way of using fashion design as a tool for critical reflection and activism within the academy. The framework is a so-called strategic subject development project at Beckmans, whose aim is to discuss the term “critical fashion practice” and highlight the critical potential of fashion practice with specific focus on non-conforming gender expression. Besides texts that address different critical perspectives in a fashion/design context, the project consists of portfolios created by former fashion students and other creatives connected to the subject and the school. This interview with Adam Swärd is the first to be published within the project, since its inception last year.

Maria Ben Saad: Why did you choose to participate in the showcase of your own graduation show?

Adam Swärd: The decision wasn’t a given. At the start of the project I was hesitant, although the concept is based on myself. But then my supervisor, Marina Kereklidou, convinced me. In the end it felt like the right way to convey the self-actualization that is at the core of the collection: to be the best version of myself and hopefully inspire others to do the same.

MBS: Your graduation collection is entitled Mada, Adam written backwards. How would you describe Mada, and Mada in relation to Adam?

AS: Mada is someone I actually want to be. I see Mada as a kind of personification of my creativity, my wish to be something more than Adam. You could call it an aspiration. Mada is a character who is ruthlessly glamourous, extravert, and doesn’t apologize for what they look like or how they dress. Mada is also full of a lust for life, leaving worries behind. Mada should be like a taste of freedom.

MBS: Is freedom something you think is missing in real life? Is there a gap between the catwalk character Mada and Adam in reality?

AS: In a way, I suppose. Because the collection is so non-normative. For example, I made a very sensual silk dress that shows a lot of skin and placed it on a male-coded body – there is a kind of vulnerability, fragility in Mada. It’s fine to dress like Mada on the catwalk, but certain spaces could be threatening, which prevents me from being Mada. “You shouldn’t wear this because it doesn’t belong to you.” Some garments are meant only for certain bodies and going against these norms can provoke people. Quite small deviations are often enough, since the rules that uphold the notion of masculinity are rigorous: shorts may not be too short nor necklines too plunging, for example.

MBS: Does the challenge mostly lie in the combination of garment and body?

AS: I’ve tried to create clothes that are stereotypically beautiful in terms of material and cut, so as to be inviting for people. They aren’t critical of the norm per se, but need a certain body for the point of the collection to emerge. It’s also a matter of styling. The silk dress, for example, has the sign of non-binary gender identity in Swarovski crystals as a detail on its back. Without that detail it’s just a pretty dress.

MBS: How important do you think it is that you yourself are part of what you describe and want to communicate with your project?

AS: I think it’s very important. Especially because, by being one of the models, I manifested what I am speaking about and didn’t just visualize a dream. This is what fashion often does otherwise – present dreams that we are supposed to strive for but never reach. By participating in the show, I demonstrated that it’s quite possible to be Mada, on my own terms. And that’s how I want Mada to function: as proof of the fact that you can be whoever you want to be. I think it would have become too abstract for others to relate to, if I hadn’t included myself.

MBS: How did the models relate to your concept? What casting process did you use?

AS: The most important thing for me was to work with models that were part of my world. They didn’t necessarily have to define themselves as non-binary, but almost all the models belonged to the LGBTQ+ community. The starting point of my research was always the Mada character and I tried to find people who could come up with their own interpretations of what Mada stands for: self-actualization and a kind of celebration of one’s own self. I recruited several models via Instagram and social media, while others were people I knew from before. I found one of the models via a casting we held at the school. They were all so good, really perfect!

MBS: Do you think that the fashion scene lacks a space where you can feel that you belong or are represented?

AS: There’s most definitely a lack here in Stockholm. But internationally there are designers who work with an aesthetic that I can relate to. Palomo Spain and Ludovic de Saint Sernin come to mind. They seem to have a target audience that exists in reality. The ballroom scene in New York with its mix of catwalk and club is also something I can relate to, since it is built around self-actualization and celebrating one another. It’s in spaces like these that I think Mada would work best.

MBS: I know you follow the TV series Pose, which has been commended for its representation and authentic casting. What does that mean in this context?

AS: I think one should always work with the authenticity that can be found in Pose. If it’s a story about the LGBTQ+ community it should be told with the people from that group. By virtue of its authenticity, the actors in Pose can use their public position to lift their entire community in a way that hasn’t been done before on the same level. There are non-binary models working in the industry who work for both men’s and women’s fashion, but non-binary collections are not an established scene. It isn’t a separate category but non-binary fashion largely exists on the terms of others. I think, for non-binary fashion to become established one needs to think long-term and for several designers to deliberately work in a similar way and establish a genre.

MBS: Is it your ambition that one should be able to wear the same kinds of garments irrespective of gender?

AS: I don’t think that there needs to be a difference. I suppose that’s my goal. If I started my own brand I wouldn’t want to be known as a designer for just men or women – I want to make clothes for everyone, regardless of gender. Often, when there’s talk of cross-gender fashion, it leans towards the masculine, towards power dressing for women, so to say. A feminine-coded aesthetic on a man doesn’t have the same power, because the feminine has traditionally been subordinate to the masculine. In future, I hope that these dichotomies will lose their meaning. I would, for example, like to see a large, manly man in something that is feminine-coded without it being derisive. It’s more tolerated for slighter men’s bodies to be feminine.

MBS: In the late 1990s, Hedi Slimane and Raf Simons challenged the norms of manliness with slimmer silhouettes for men. What do you think of fashion’s ability, in general, to bring about change in society?

AS: I strongly believe that fashion has this power. How we see our bodies and ourselves changes with fashion. And, of course, changes in fashion work hand-in-hand with movements in society. Fashion, I think, is like a gateway. Change becomes concrete in fashion since we have to deal with it every time we get dressed. As consumers we can influence in which direction we want society to go.

MBS: What ability to influence do you think you have? Mada is something that you also personify on your Instagram account, for example.

AS: On my account I stage myself as I see myself. It’s where I can most easily show “this is me.” And, of course, it has a connection to my self-actualization, because you can’t always decide for yourself how other people see you. My Instagram feed has made me feel included. I have come in contact with like-minded people from around the world and we support each other. We create this space for ourselves that is missing in reality, or at least in Stockholm. It’s meaningful, even though it’s not real. It’s kind of like, “I’ve got your back.”

MBS: To round off, can you say something about how this Mada character came about or was formulated visually for the show?

AS: The whole thing started when I had a little workshop for myself in my apartment ahead of my graduation show. I gathered toiles from a preparatory course and chose a dress that I put on to create an atmosphere around me and what I would look like. Then I took a photo of myself in the dress with a pair of heels and slicked-back hair and posted it on Instagram with a background text. I wanted a public reaction and I noticed that the image provoked a lot of interest, and in fact only positive reactions. And then I was contacted by a photographer, Tony Ottosson, whom I had done a commercial modelling job with before, completely without norm-critical ambition. We started exploring ideas about how we could develop what I had started and decided to do a staging that looked back to when I was younger and was always getting dressed up in anything I could put my hands on, from princess dresses to cowboy boots. Based on that we did a whole photo shoot in which we played with different expressions until I found what became Mada.

Maria Ben Saad is a fashion writer and lecturer of Fashion Theory at Beckmans College of Design. She is also responsible for the project mentioned in the text.

Adam Swärd’s graduation collection Mada can be seen on Beckmans’ website, beckmans.se and on Instagram (_adamsvaerd). The photos were taken by James Whitmore. Translation from Swedish by Bettina Schultz. This interview was published in our 10 year anniversary issue.