Byronesque and the Value of Fashion History

By Marco Pecorari

Fashion archives are living in a new era. Not only are luxury fashion brands investing in rebuilding their own past, but a new definition and consumption of vintage clothing is emerging. The revival of the past has become more than an expression of nostalgia. Rather, it is an answer to today’s mass production and consumption. We asked Gill Linton, co-founder of Byronesque – the online editorial-based shop for contemporary vintage fashion – to lead us through the intricate world of ‘future vintage’. Together we reflect on the practice of commercialising the past and its potential for reaffirming values that the fashion industry has forgotten, but that may come back.

When did your passion for ‘vintage’ start?

I was a teenager in the 1980s and count myself lucky to have witnessed and copied the New Romantics. I wasn’t old enough to make it to the Blitz Club, but I tried very hard to look like I would get in. I looked like something between Bananarama and the girls from the Human League, which I wish were true today. I grew up in a very creative, free time when people where more independent and played with fashion, rather than pandering to it. Over the years, I have worked with a lot of fashion brands to help them figure out how to be different from each other (the design and brand bit) but I got bored of everything staying the same and only found inspiration in the past. I started Byronesque in the spirit of the 1980s and the New Romantics and to make certain archival clothes are as exciting and accessible as fashion should be today. We have a ruthless belief that just because it’s old doesn’t mean it’s good. But I hated vintage shops. The thrill of the find was never a thrill for me. It had to be easier.

How did Byronesque start? What were your early ambitions?

The official answer is that the really good stuff was hard to find. At the time – we started in 2013 – if you wanted a boho maxi dress from the 1970s or a Chanel chain bag, it was pretty easy to find. And if you had the budget, even vintage couture was easy to find. But the really modern, extraordinary and creative stuff by designers, some of whom were and are still designing, and those who weren’t … that wasn’t easy. We solved the supply and demand problem. I wanted Westwood punk or ’90s Comme and it was hard to find amidst the crap and couture. Our ambition was to be an influence brand in fashion that championed the past to improve ideas.

The unofficial answer is that it started painfully. No one believed that old clothes could be luxury and that people would pay a lot of money for them. No one believed that people would value vintage emotionally and financially in the way they do now. No-one invested in us. Until they did.

With Montana you started a series of ‘reissue’ collections. What is the idea behind them and how does the process of making them work?

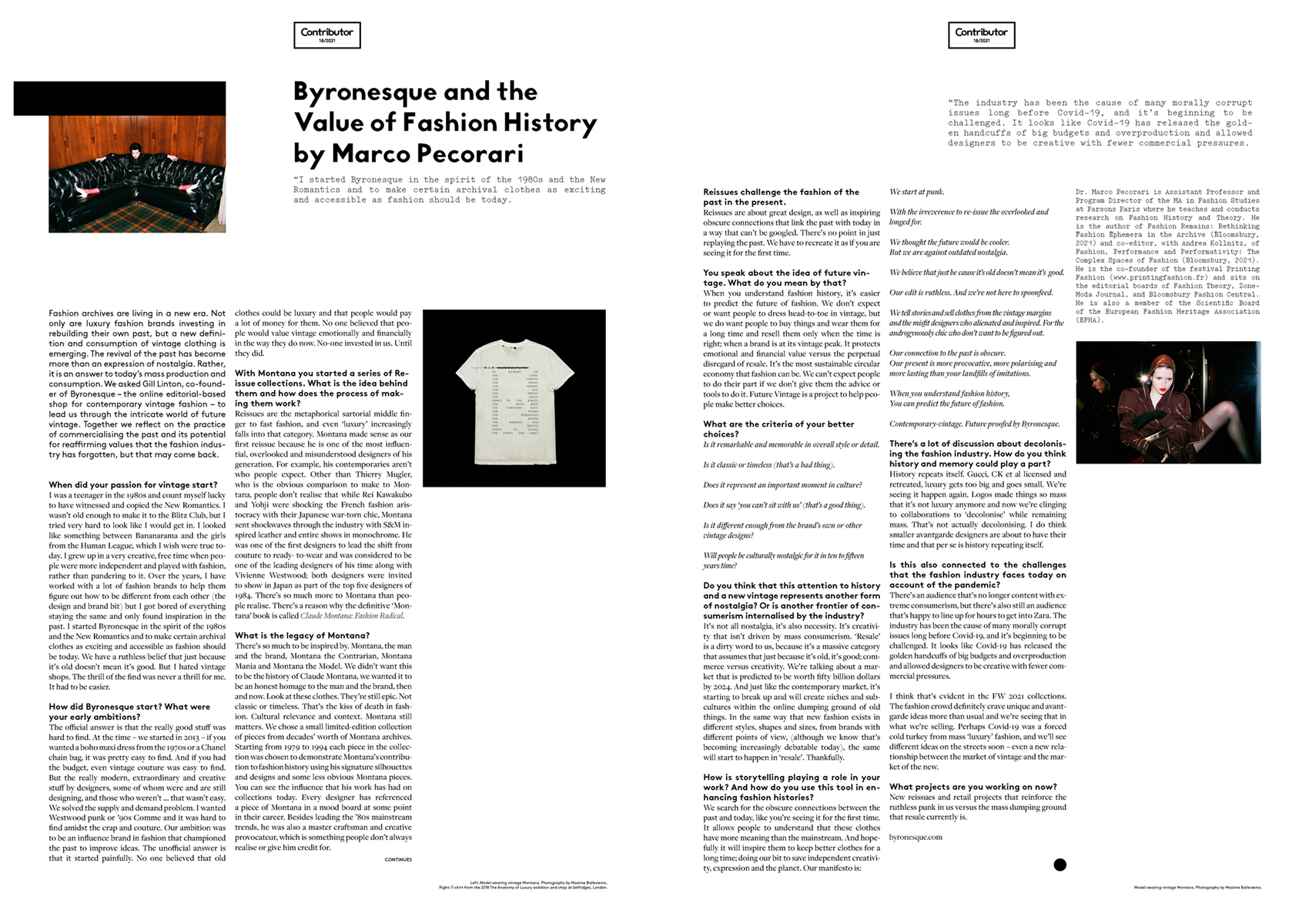

Reissues are the metaphorical sartorial middle finger to fast fashion, and even ‘luxury’ increasingly falls into that category. Montana made sense as our first reissue because he is one of the most influential, overlooked and misunderstood designers of his generation. For example, his contemporaries aren’t who people expect. Other than Thierry Mugler, who is the obvious comparison to make to Montana, people don’t realise that while Rei Kawakubo and Yohji were shocking the French fashion aristocracy with their Japanese war-torn chic, Montana sent shockwaves through the industry with S&M inspired leather and entire shows in monochrome. He was one of the first designers to lead the shift from couture to ready-to-wear and was considered to be one of the leading designers of his time along with Vivienne Westwood; both designers were invited to show in Japan as part of the top five designers of 1984. There’s so much more to Montana than people realise. There’s a reason why the definitive ‘Montana’ book is called Claude Montana: Fashion Radical.

What is the legacy of Montana?

There’s so much to be inspired by. Montana, the man and the brand, Montana the Contrarian, Montana Mania and Montana the Model. We didn’t want this to be the history of Claude Montana, we wanted it to be an honest homage to the man and the brand, then and now. Look at these clothes. They’re still epic. Not classic or timeless. That’s the kiss of death in fashion. Cultural relevance and context. Montana still matters. We chose a small limited-edition collection of pieces from decades’ worth of Montana archives. Starting from 1979 to 1994 each piece in the collection was chosen to demonstrate Montana’s contribution to fashion history using his signature silhouettes and designs and some less obvious Montana pieces. You can see the influence that his work has had on collections today. Every designer has referenced a piece of Montana in a mood board at some point in their career. Besides leading the ’80s mainstream trends, he was also a master craftsman and creative provocateur, which is something people don’t always realise or give him credit for.

Reissues challenge the fashion of the past in the present.

Reissues are about great design, as well as inspiring obscure connections that link the past with today in a way that can’t be googled. There’s no point in just replaying the past. We have to recreate it as if you are seeing it for the first time.

You speak about the idea of ‘future vintage’. What do you mean by that?

When you understand fashion history, it’s easier to predict the future of fashion. We don’t expect or want people to dress head-to-toe in vintage, but we do want people to buy things and wear them for a long time and resell them only when the time is right; when a brand is at its vintage peak. It protects emotional and financial value versus the perpetual disregard of resale. It’s the most sustainable circular economy that fashion can be. We can’t expect people to do their part if we don’t give them the advice or tools to do it. Future Vintage is a project to help people make better choices.

What are the criteria of your ‘better choices’?

IS IT REMARKABLE AND MEMORABLE IN OVERALL STYLE OR DETAIL.

IS IT CLASSIC OR TIMELESS (THAT’S A BAD THING).

DOES IT REPRESENT AN IMPORTANT MOMENT IN CULTURE?

DOES IT SAY ‘YOU CAN’T SIT WITH US’ (THAT’S A GOOD THING).

IS IT DIFFERENT ENOUGH FROM THE BRAND’S OWN OR OTHER VINTAGE DESIGNS?

WILL PEOPLE BE CULTURALLY NOSTALGIC FOR IT IN TEN TO FIFTEEN YEARS’ TIME?

Do you think that this attention to history and a new vintage represents another form of nostalgia? Or is another frontier of consumerism internalised by the industry?

It’s not all nostalgia, it’s also necessity. It’s creativity that isn’t driven by mass consumerism. ‘Resale’ is a dirty word to us, because it’s a massive category that assumes that just because it’s old, it’s good; commerce versus creativity. We’re talking about a market that is predicted to be worth fifty billion dollars by 2024. And just like the contemporary market, it’s starting to break up and will create niches and subcultures within the online dumping ground of old things. In the same way that new fashion exists in different styles, shapes and sizes, from brands with different points of view (although we know that’s becoming increasingly debatable today) the same will start to happen in ‘resale’. Thankfully.

How is storytelling playing a role in your work? And how do you use this tool in enhancing fashion histories?

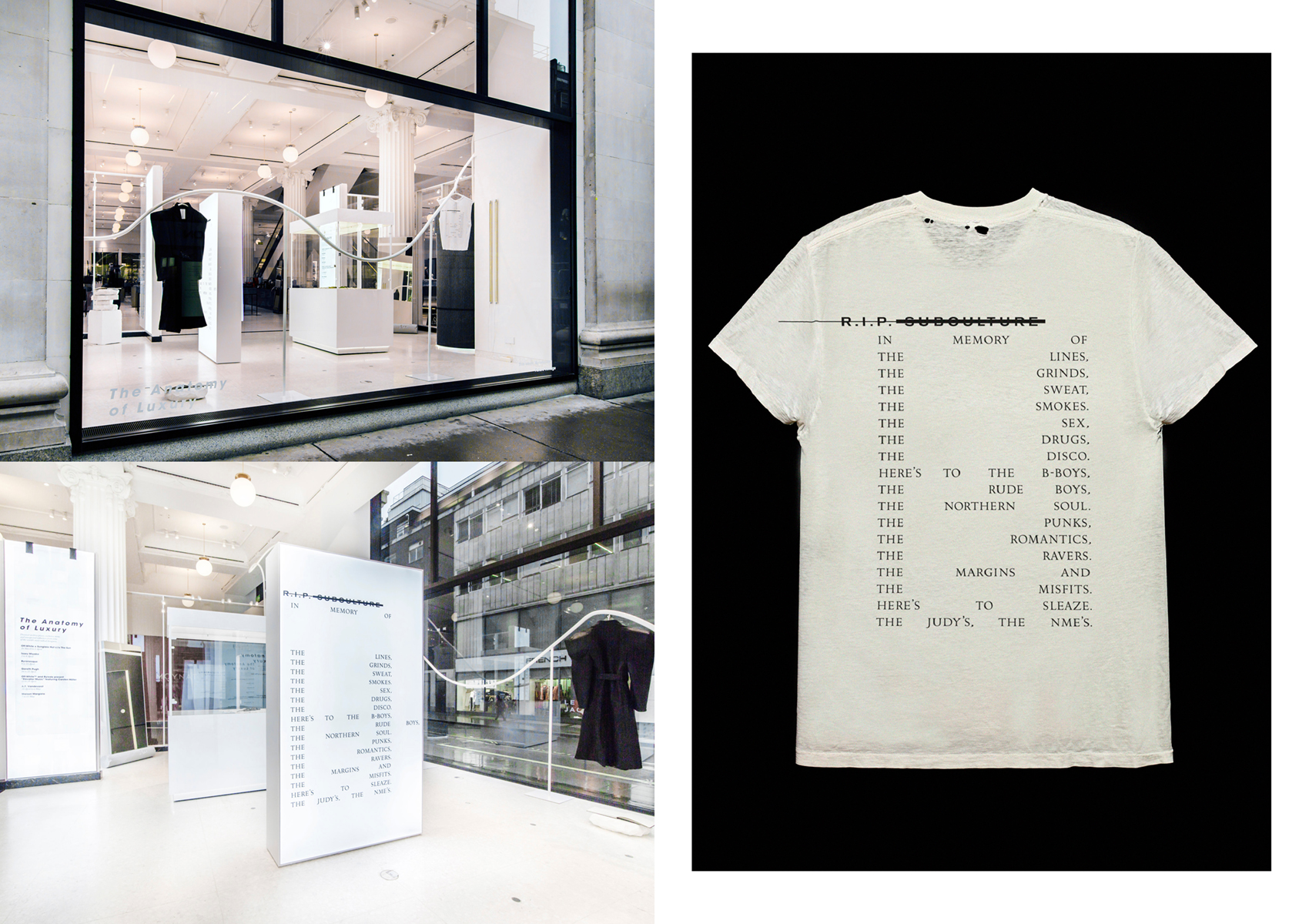

We search for the obscure connections between the past and today, like you’re seeing it for the first time. It allows people to understand that these clothes have more meaning than the mainstream. And hopefully it will inspire them to keep better clothes for a long time; doing our bit to save independent creativity, expression and the planet. Our manifesto is:

WE START AT PUNK.

WITH THE IRREVERENCE TO RE-ISSUE THE OVERLOOKED AND LONGED FOR.

WE THOUGHT THE FUTURE WOULD BE COOLER. BUT WE ARE AGAINST OUTDATED NOSTALGIA.

WE BELIEVE THAT JUST BECAUSE IT’S OLD DOESN’T MEAN IT’S GOOD. OUR EDIT IS RUTHLESS. AND WE’RE NOT HERE TO SPOONFEED.

WE TELL STORIES AND SELL CLOTHES FROM THE VINTAGE MARGINS AND THE MISFIT DESIGNERS WHO ALIENATED AND INSPIRED. FOR THE ANDROGYNOUSLY CHIC WHO DON’T WANT TO BE FIGURED OUT.

OUR CONNECTION TO THE PAST IS OBSCURE. OUR PRESENT IS MORE PROVOCATIVE, MORE POLARISING AND MORE LASTING THAN YOUR LANDFILLS OF IMITATIONS.

WHEN YOU UNDERSTAND FASHION HISTORY, YOU CAN PREDICT THE FUTURE OF FASHION.

CONTEMPORARY-VINTAGE. FUTURE PROOFED BY BYRONESQUE.

There’s a lot of discussion about decolonising the fashion industry. How do you think history and memory could play a part?

History repeats itself. Gucci, CK et al licensed and retreated, luxury gets too big and goes small. We’re seeing it happen again. Logos made things so mass that it’s not luxury anymore and now we’re clinging to collaborations to ‘decolonise’ while remaining mass. That’s not actually decolonising. I do think smaller avantgarde designers are about to have their time and that per se is history repeating itself.

Is this also connected to the challenges that the fashion industry faces today on account of the pandemic?

There’s an audience that’s no longer content with extreme consumerism, but there’s also still an audience that’s happy to line up for hours to get into Zara. The industry has been the cause of many morally corrupt issues long before Covid-19, and it’s beginning to be challenged. It looks like Covid-19 has released the golden handcuffs of big budgets and overproduction and allowed designers to be creative with fewer commercial pressures.

I think that’s evident in the FW 2021 collections. The fashion crowd definitely crave unique and avantgarde ideas more than usual and we’re seeing that in what we’re selling. Perhaps Covid-19 was a forced cold turkey from mass ‘luxury’ fashion, and we’ll see different ideas on the streets soon – even a new relationship between the market of vintage and the market of the new.

What projects are you working on now?

New reissues and retail projects that reinforce the ruthless punk in us versus the mass dumping ground that resale currently is.

Byronesque is the online editorial-based shop for contemporary vintage fashion.

Dr. Marco Pecorari is Assistant Professor and Program Director of the MA in Fashion Studies at Parsons Paris where he teaches and conducts research on Fashion History and Theory. He is the author of Fashion Remains: Rethinking Fashion Ephemera in the Archive (Bloomsbury, 2021) and co-editor, with Andrea Kollnitz, of Fashion, Performance and Performativity: The Complex Spaces of Fashion (Bloomsbury, 2021). He is the co-founder of the festival Printing Fashion and sits on the editorial boards of Fashion Theory, ZoneModa Journal, and Bloomsbury Fashion Central. He is also a member of the Scientific Board of the European Fashion Heritage Association (EFHA).