Pictures courtesy of Company Gallery New York.

Pattern of Thoughts. Interview with Linnéa Sjöberg

She exposed her body to incredible physical and mental pressure in two performative works that lasted around the clock for five years. The artist Linnéa Sjöberg documents her captivating practice using textiles, sculptures, printmaking, text and sound. Her art challenges our experience of time and memory. It raises questions about society and the transfer of knowledge, and lays bare the construction of identities and the materiality of things.

By Antonia Nessen

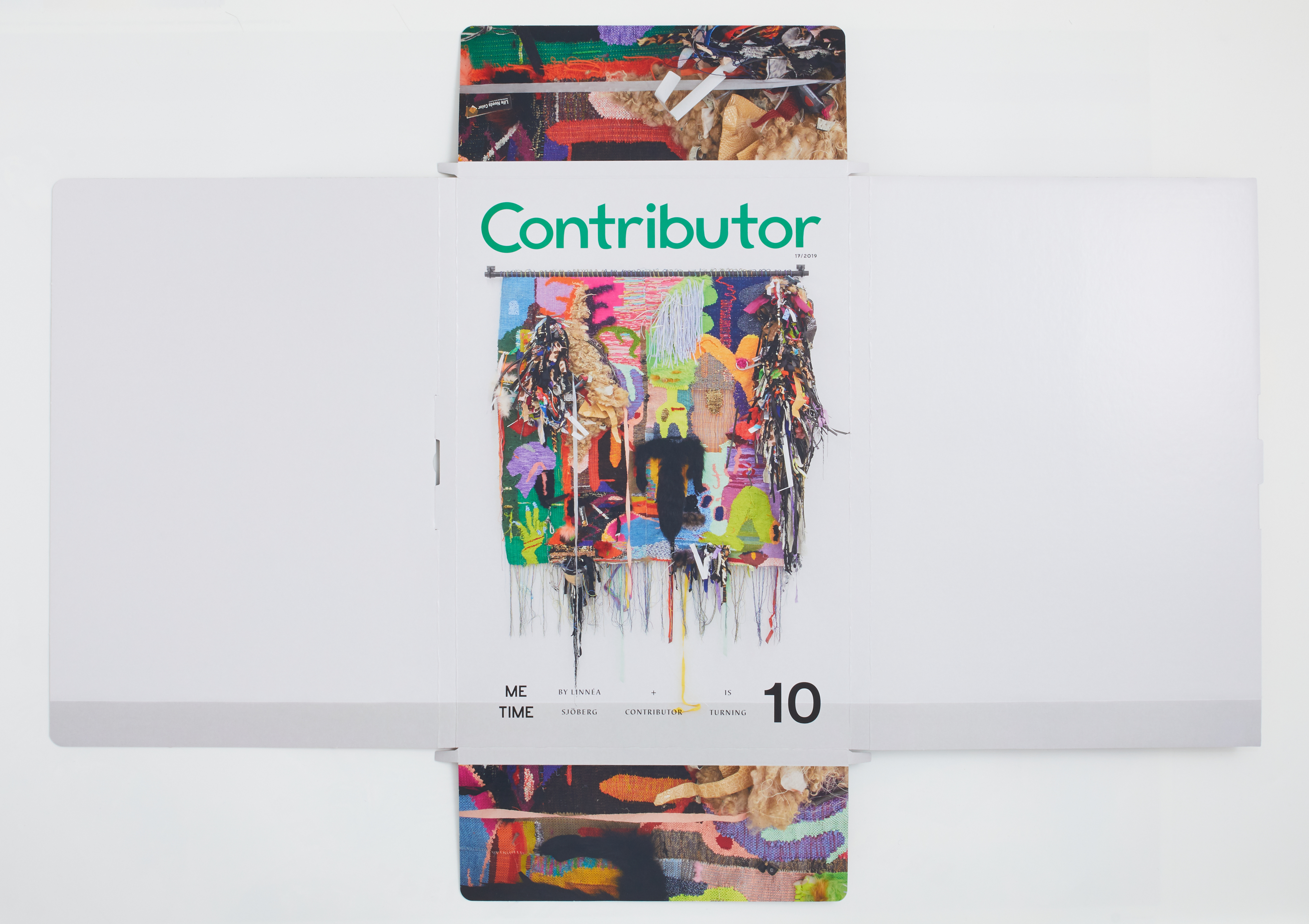

“The latest weaves are called Pattern of Thoughts. They don’t have any predetermined patterns, rather they are a kind of visualization of how my brain works when I weave. I try to have lots of fun in my studio and be curious about where my thoughts will lead me,” says Linnéa Sjöberg, who has been working in Berlin since 2016 and is busy preparing for a solo exhibition at Company Gallery in New York.

In what way is Pattern of Thoughts different from your previous work?

“All my work has been based on personal experience, exposing myself to things. For my first pieces I used a loom mainly to deconstruct material that has memories and sentimental value,” says Linnéa.

For Four Generations of Darkness (2016), Linnéa plundered the attic of her childhood home in search of dark material. The resultant fourteen-meter-long piece includes textiles from old clothes, and other material, which she cut and rolled up before weaving them together. Deutsche Welle (2017) is another example of how she uses her loom as a tool to take away the function of the original material and “erase” information. Here she worked with our collective memories and the media images that shape our consciousness, making a number of weaves using the magnetic tape from the VHS archive at the German TV channel Deutsche Welle. One of the works in the series, German Wave III, was acquired by Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

“I find myself in a kind of transitional phase. After weaving for a while, the material doesn’t need to have a trace in itself or any of my personal memories any more. It’s material that I have bought to weave with. What can I talk about when I make a weave?”

The reason why Linnéa started weaving was to shred, encapsulate, and reconstruct the career woman. Linnéa destroyed her entire wardrobe and wove the material together again when she made The Remains of a Business (2015) consisting of eleven rag rugs the same size as Linnéa’s waist and height, in high heels. For a year and a half, she lived as Career Woman GTD4s810 (Getting Things Done for Satan) twenty-four hours a day. The work was conceived in 2009 as a reaction to the art world when she was a student at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm.

“It terrified me when I realized how the art scene worked. People were careerists, you were expected to be strategic, talk to important curators and professors. In an act of pure resistance, I walked straight into what I was most afraid of. So I became my own opposite, the kind of person I would normally never interact with.”

In the process of making the work, Linnéa vacuum-packed her ordinary black clothes, leather jackets, baseball caps, and hoodies, covered her tattoos with make-up, dressed in pressed designer clothes, pearl earrings, and coiffed blond hair, in order to exude success and confidence. The transformation took over her entire life until it was no longer possible to differentiate between the fictitious character and Linnéa’s original self. The work came about in contact with many other people, like when a stranger tapped her on the shoulder in a luxury boutique in central Stockholm and asked her questions about her handbag since she was on Hermès’ waiting list to buy the same model. Apart from the rag rugs, Linnéa also made sculptures from the fragments. She threaded scrap metal pieces onto the underwire of bras to make portraits on the gallery wall while her tattered pumps were mounted with stiletto heels on stones that she had collected in northern Sweden, where she grew up.

“I constantly come back to my relationship with clothes, codes, and identities,” says Linnéa, who started weaving to connect to memories of her grandmother Elvy, who would repurpose old rags, textiles, and other leftover materials.

“My grandmother made rugs out of old clothes, and other people in the village ordered rugs from her, so she wove to make money. But she stopped when my mother was young. I grew up surrounded by her rag rugs.”

What made you start looking back?

“I spent five years focused exclusively on other identities and when I came out from that I didn’t have much left, in the present, after making Career Woman and Salong Flyttkartong. I was quite empty, so it has been a natural process for me over the past few years to backtrack myself. I feel safe with textiles because I have always been surrounded by them,” says Linnéa.

After concluding Career Woman GTD4s810, it was not long until she initiated Salong Flyttkartong. She bought a tattoo machine during a trip to New York and worked according to the motto “act before you think.” She shaved off most of her hair, brewed her own beer, and set up an ambulatory tattoo parlor in basements, outdoors, or at friends’ houses. The work was unique, humorous, at times repulsive, and caused quite a stir. Certain established tattoo artists regarded Linnéa’s tattoos as fake and reported her to the Swedish authorities. Writing about the tattoo artists who wanted to stop her from working, a reviewer aptly stated: “they may not be good tattoos but it’s damn good art.”

“It was all born out of a feeling of resistance to not being allowed to participate, to being left out; it was like an anti everything. I stopped when Salong Flyttkartong was accepted by the establishment and invited to an art gallery and a museum.”

After occupying herself with human skin for two years for Salong Flyttkartong she became interested in the leftover material from the making of leather products. When she worked at a tannery and made leather embossing, she started wetting, kneading, and rolling up second-hand clothes and garbage in cowhide, which she left to dry into fascinating sculptures for the series The Inward Dance.

When we met for this interview, the exhibition Smetana Disc Brake was being held at an exhibition space on the outskirts of Stockholm and one of the cowhide sculptures was included, placed on a pile of matted sheep’s wool, sewn together with copper wire, with visible electric wires, and wearing a black patent leather shoe and a sneaker. Every now and again, a man’s voice echoed through the exhibition space. This was Linnéa’s sound piece Den Schnee Lesen/Läsning av Snö (2018), based on childhood memories. It’s an ongoing work in which she meets her father in order to try to understand the coded reality that he sees as an active radio amateur.

“My father can see and hear Morse code in everything that makes a sound or moves, because Morse code is made up of rhythms, long and short tones. So when I was a child, I got him to interpret falling snow for me. We’ve done a few sessions where we sit in his car and he uses his radio equipment to send the letters he sees when he looks at the snowflakes falling onto the windscreen. I record it and then we translate it into letters again. So, no words are formed, just a flow of letters.”

Linnéa grew up with her family in the northern-most part of Sweden. Her mother is a teacher and has one of Linnéa’s tattoos on her arm. “Thousand” written in Morse code. It’s Linnéa’s father’s nickname. Her hometown, Strömsund, is idyllically situated, close to water, forests, and mountains, with wood-related industries and winter sports. Snowmobiles, ice fishing, and skiing.

“It wasn’t a countrified childhood. It was an ordinary house in an ordinary neighborhood. I had two cats and the forest started where our property ended with mountains on the horizon.”

When she thinks back it’s with mixed feelings. Although her parents always knew that Linnéa would do her own thing, the rest of small-town life was rather limiting. The atmosphere was stifling at times.

“Growing up, I developed a kind of chameleon-like behavior in order to survive. That’s probably why I find a sense of security in just disappearing into another identity. I was severely bullied. I was always the smallest, always sick. My teachers wanted to move me down a grade and the doctors didn’t think I would make it past the age of five.”

Linnéa nearly didn’t make it into the world because her mother almost went into labor in her fourth month. As a result of complications during birth, a variety of pediatricians speculated that she may not develop normally. The fact that Linnéa learnt to see her body as a problem from a young age may be the reason why she has needed to take control over it as an adult.

“As a result, I’ve had the attitude: ‘Then it should get even more of a beating, goddammit!’”

But Linnéa also grew up with a deep understanding of her maternal grandparents and their experiences. Sitting around the kitchen table as a twelve- or thirteen-year-old, she understood that she was privileged, that she would have opportunities that her older relatives never had access to. Linnéa is one generation removed from two minority groups that have been historically marginalized and discriminated against in Sweden: the indigenous Sami population and the Finland Swedes. Last summer Linnéa restored her grandmother’s loom, which had been lying disassembled in the attic. The feeling of reactivating the loom that her “momma” had sat at forty years ago was incredibly powerful. Elvy lived to over ninety and died the same summer that Linnéa started weaving.

“When I’m sitting and weaving it’s about making a piece,” says Linnéa. “It’s also been great to create an object outside the body.”

Just like in her other works, Linnéa has gone “all in” and become totally absorbed by weaving. When Linnéa left Stockholm and moved to Berlin three years ago she planned to go to exhibitions, socialize, and meet people, but quite the opposite happened. Instead she has locked herself in, completely stopped drinking alcohol, and just worked.

“I have gone so far into isolation through the weaving. I can hardly find my place within city life anymore. I have noticed that I am sitting still for the first time in my life and that there’s no one around. The loom has become like some kind of fortress.”

In order to go even deeper into the weaving, Linnéa developed a third character. The fact that Linnéa has often dissected our linear sense of time and the objects we appoint as bearers of the past became particularly clear when she embarked on The Viking Woman. But this time it was a bit of a coincidence. She decided to reenact a role, make a costume, and try to relate historically to how women dressed in prehistoric times so she could get closer to a certain type of loom.

“I’m sitting in a classic loom in which one sits and weaves horizontally. Why does it look the way it does? I started tracing the history of weaving and its development in Scandinavia and stumbled on archeological finds from around the Viking Age. I became obsessed with the thought of learning to weave on a warp-weighted loom.”

It’s a kind of smaller-scale standing loom with roots in ancient Greece. Linnéa got in touch with a museum and was invited to work on their active looms. The method meant that the actual process became an important element in the work. As opposed to Career Woman GTD4s810 and Salong Flyttkartong, Linnéa worked with a reenactment where she could enter and exit a role without having to leave behind her real persona.

“It turned into a kind of shift from previously letting my identity change and the work take over my life to embarking on a similar process but within a structure where I could go in and out of it. What happens if I see the career woman as a reenactment?”

Linnéa adds that she still asks herself: “Why do I do this? I always think that if I can challenge my own work process, if I can break it apart and move on, then I’m on the right path.”

Are you going to continue working with The Viking Woman?

“I’ve put her aside. She was necessary to get closer to the loom, but where else should she be? In that case I would have to go out into the forest and never come out – that’s where she belongs.”

For more information on the artist Linnéa Sjöberg, visit linneasjoberg.com. Translation by Bettina Schultz