Director Ruben Östlund won the Palme d’Or for “The Square” at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. To mark the occasion, we publish this interview from our “Nature is culture” issue where Ruben talks about his award-winning film featuring Claes Bang, Elisabeth Moss and Dominic West.

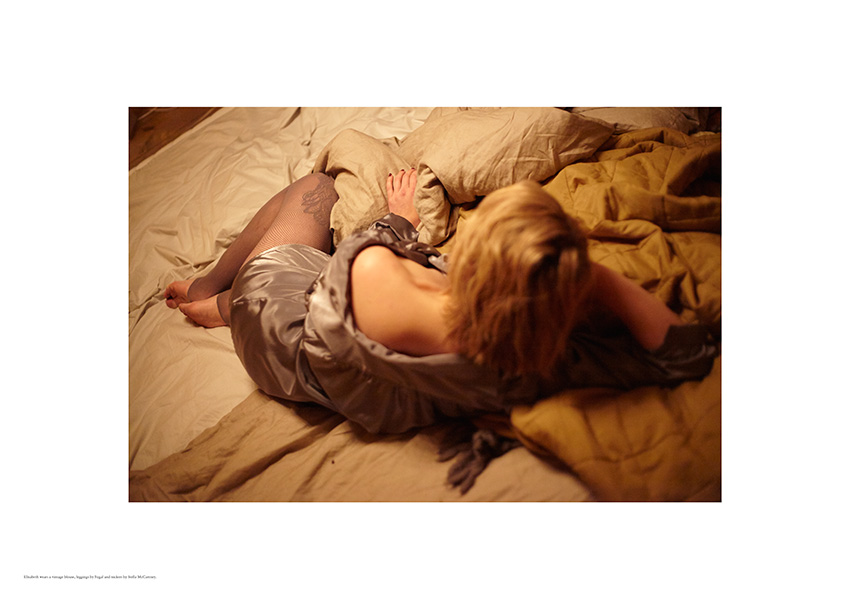

By Jon Asp. Photography by Ruben Östlund and styling by Sofie Krunegård

Last time I met with Ruben Östlund was at the Cannes Croisette in May 2016, where the Swedish director allowed himself the luxury to immerse in the world of film, taking precious time off from his own ongoing production. To be in one of the juries of the festival was an offer to good to resist. Cannes is after all Östlund’s favorite festival and the primary goal for every film he releases.

A half year later I got hold of him by phone on the Isle of Capri outside Napoli. There he was editing his fifth feature at Villa San Michele, classical residence for Swedish artists. After nearly a month he was still working on the scene he first started with. Somewhat the panic was starting to spread. The time delay was due to one advanced sequence, where a performance artist was to receive a royal prize at a pompous ceremony in Stockholm. Played by Terry Notary, the motion capture performer known for his work in the “Planet of the Apes” films, the artist also gave an imposing ape imitation. But the show got out of control.

“The scene is very central to the film and there are so many options. Also Terry makes a very strong performance, wherefore I am obliged to put a lot of time and effort into it.”

“The Square” is the title of the film, and also the name of an art installation that refers to a special zone where all visitors have equal rights and responsibilities. The main protagonist is a museum manager played by Danish actor Claes Bang, who hires two unabashed PR consultants to create attention around the installation. Alongside, the manager is subjected to a scam, when having his mobile phone stolen in the street. This event, experienced by Östlund, triggered the very idea of the film, a scene that forces the well-off people to confront individuals from a different socioeconomic sphere.

“I’m interested in the same kind of feelings and emotions that I have always been into, the comical and the uncomfortable, with a constant feeling of something awkward. I want to raise questions on situations that are hard to cope with.”

One of contemporary Scandinavia’s most respected film directors is known for his topic-driven works with self-contained role characters afraid of losing appearances when confronted with moral dilemmas in public spaces. “The Square” is no exception to that. Unlike fellow countryman Tomas Alfredson, celebrated Danish directors, Lars von Trier, Tomas Vinterberg, Lone Scherfig, Nicholas Winding-Refn, Norwegian wunderkind Joachim Trier, Östlund stays faithful to his home soil on the Swedish west coast, where he still lives and runs his acclaimed production company Plattform.

Not that there is a lack of offers from abroad. His previous film, the ski resort comedy-drama “Force Majeure” had an overwhelming reception at Cannes in 2014, won the Un Certain Regard jury prize, and moved on to a fortunate theatrical play worldwide. In the US, Östlund was also attributed a retrospective, including his award-winning shorts, at respected venues all over the country. Not bad for a then 40-year-old director, growing up on a religious island in the archipelago outside the industrial city of Gothenburg, and who started his creative path by making skiing films in the 1990s. His way to the top has not always been straight, or conventional, the director as an observer of human behavior on YouTube rather than in film history. Nevertheless, Östlund has drawn imperative inspiration from the headstrong Swedish veteran filmmaker Roy Andersson, and early on he acknowledged his admiration for Michael Haneke’s films. Today, Östlund is one of a few Swedish art-house directors capable of attracting a wider audience.

His success has not come unnoticed. “The Square” includes a bunch of well-known international actors, from “Top of the Lake” star Elisabeth Moss, who had her breakthrough as the farsighted but repeatedly prevented Catholic secretary Peggy Olsen in “Mad Men,” to Britain’s Dominic West, known for his leads in “The Wire” and “The Affair,” and handpicked by Östlund for his distinctive aptitude for alpha males. After the shooting in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Berlin in early autumn, Ruben Östlund admits it was not an easy game to handle these stars. The director is known for his rigorous way of working on set, with long scenes and a high number of takes.

“Some of the Scandinavian actors had a certain knowledge of my method beforehand, whereas the international actors were in complete shock. After the first day Dominic West asked, after about thirty takes of the same scene: ‘Do you always work like this?’ No matter how much I tried to underline my method during the casting process, they still came to Sweden with the idea of having a vacation, shooting one scene per today. But not until getting the experience on set, they understood how it worked, and still it meant a big adjustment for them.”

After a few days of customary tiptoeing some irritation had to be let out, and Ruben Östlund was very happy with the outcome. “Elisabeth was awesome. I am very pleased with what she became. I am sure she will be an excellent character. Not until you lose some respect for the actors, you are able to push and provoke the things you really want. And then they also felt assured in the situation, and thus were able to deliver the scenes.”

Being to Cannes with three out of his four previous films, it comes as no surprise that he is aiming to go there again in 2017. One of Östlund’s prescriptions is not to adapt too much to an international context.

“In order to let the film travel abroad, it is really important to trust in the local elements which I have explored before. I believe most people around the world are somewhat interested in the Scandinavian society, and like to reflect themselves in that, just as Swedish people reflect themselves in other countries.”

Ruben Östlund does not shy away from crediting his profession. “Being a film director is by far the most demanding artistic work, because you are under a lot of psychological pressure, responsible for a machinery that costs a quarter of a million each day. You must be assured enough to let go, and at the same time dare take wild decisions when nothing occurs on the set. Damn, I have respect for this job, and the more I practice it the more respect I get.”

Jon Asp is a film critic, editor of the Swedish film magazine POV and a contributor to Variety.