Unmasking the Masquerade: fetishism, art and fashion

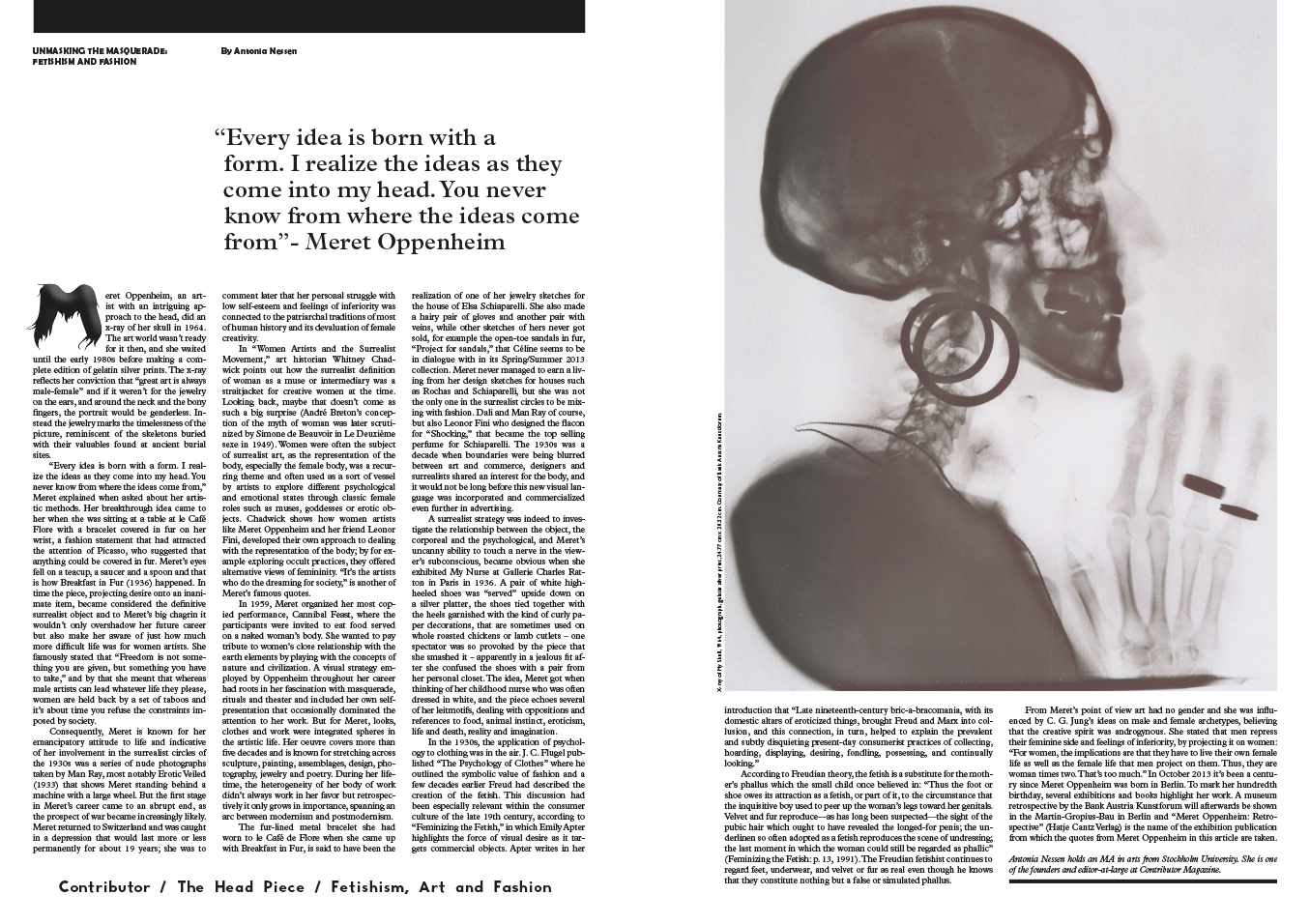

An artist with an intriguing approach to the head, Meret Oppenheim did an x-ray of her skull in 1964, when the art world wasn’t ready for it. The x-ray reflects her conviction that “great art is always male-female”.

By Antonia Nessen

“Every idea is born with a form. I realize the ideas as they come into my head. You never know from where the ideas come from,” Meret explained when asked about her artistic methods. Her breakthrough idea came to her when she was sitting at a table at le Café Flore in Paris with a bracelet covered in fur on her wrist, that had attracted the attention of Picasso. Meret’s eyes fell on a teacup, a saucer and a spoon and that is how Breakfast in Fur (1936) happened. In time the piece, became considered the definitive surrealist object, and to Meret’s big chagrin Breakfast in Fur wouldn’t only overshadow her future career, but also make her aware of just how much more difficult life was for women artists. She famously stated that “Freedom is not something you are given, but something you have to take.”

The first stage in Meret’s career came to an abrupt end, as she was caught in a depression that would last more or less permanently for about 19 years; she was to comment later that her personal struggle with low self-esteem was connected to the patriarchal traditions of most of human history and its devaluation of creativity among women. In Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, art historian Whitney Chadwick points out how women were often the subject of surrealist art, as the representation of the body, especially the female body, was a recurring theme and often used as a sort of vessel by artists to explore different psychological and emotional states through female stereotypes such as muses, goddesses or erotic objects. Chadwick shows how women artists like Meret Oppenheim and her friend Leonor Fini, developed their own approach to dealing with the representation of the body; by for example exploring medieval and occult practices, they offered alternative views of femininity. In 1959, Meret organized her most copied performance, La Festine, where the participants were invited to eat food served on a naked woman’s body. She wanted to pay tribute to women’s close relationship with the earth elements by playing with the concepts of nature and civilization. A visual strategy employed by Oppenheim throughout her career had roots in her fascination with masquerade, rituals and theater. Her oeuvre is known for stretching across sculpture, painting, assemblages, design, photography, jewelry and poetry.

The fur-lined metal bracelet she had worn to le Café de Flore when she came up with Breakfast in Fur, is said to have been the realization of one of her jewelry sketches for the house of Schiaparelli. Meret never managed to earn a living from her design sketches for brands such as Rochas and Schiaparelli, but she was not the only one in the surrealist circles to be mixing with fashion. Dali and Man Ray of course, but also Leonor Fini who designed the flacon for “Shocking,” that became the top selling perfume for Schiaparelli. The 1930s was a decade when boundaries were being blurred between art and commerce, designers and surrealists shared an interest for the body, and this new visual language was incorporated and commercialized in advertising.

A surrealist strategy was indeed to investigate the relationship between the object, the corporeal and the psychological, and Meret’s uncanny ability to touch a nerve in the viewer’s subconscious, became obvious when she exhibited Ma Gouvernante at Gallerie Charles Ratton in Paris in 1936. A pair of white high-heeled shoes was “served” upside down on a silver platter, the shoes tied together with the heels garnished with the kind of curly paper decorations, that are sometimes used on whole roasted chickens or lamb cutlets – one spectator was so provoked by the piece that she smashed it – apparently after she confused the shoes with a pair from her personal closet.

In the 1930s, the application of psychology to clothing was in the air. This discussion had been especially relevant within the consumer culture of the late 19th century, according to Feminizing the Fetish, in which Emily Apter highlights the force of visual desire as it targets sexual and commercial objects. Apter writes in her introduction that “Late nineteenth-century bric-a-bracomania, with its domestic altars of eroticized things, brought Freud and Marx into collusion, and this connection, in turn, helped to explain the prevalent and subtly disquieting present-day consumerist practices of collecting, hoarding, displaying, desiring, fondling, possessing, and continually looking.” According to Freudian theory, the fetish is a substitute for the mother’s phallus which the small child once believed in: “Thus the foot or shoe owes its attraction as a fetish, or part of it, to the circumstance that the inquisitive boy used to peer up the woman’s legs toward her genitals” (Feminizing the Fetish: p. 13, 1991). The fetishist continues to regard feet, underwear, and velvet or fur as real even though he knows that they constitute nothing but a false or simulated phallus, according to Freud that is.

From Meret’s point of view art had no gender and the creative spirit was androgynous. She stated that men repress their feminine side and feelings of inferiority, by projecting it on women: “For women, the implications are that they have to live their own female life as well as the female life that men project on them. Thus, they are woman times two. That’s too much.”

In October 2013 it’s been a century since Meret Oppenheim was born in Berlin. To mark her hundredth birthday, several exhibitions and books highlight her work. A museum retrospective by the Bank Austria Kunstforum will afterwards be shown in the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin and “Meret Oppenheim: Retrospective” (Hatje Cantz Verlag) is the name of the exhibition publication from which the quotes from Meret Oppenheim in this article are taken.

Writer Antonia Nessen holds an MA in arts from Stockholm University. She is a co-founder and editor at Contributor Magazine. This article was originally published in The Head Piece Issue (spring 2013).